– by Martin Wein – 30/4/2024

It’s now eight decades since the Shoah and nearly the same after the First Nakba of 1948. The Shoah has been the textbook case of genocide, and the most documented and well-researched case — although probably not the largest, even if we add the millions of Christian victims, specifically Slavs and Romanies. The global genocide quantitative listing is usually topped by British rule in India and Mao’s rule in China, followed by Genghis Khan and Stalin. The Shoah was unique in Jewish history, but not in a global historical perspective in my view. Each of its aspects may be found elsewhere.

The First Nakba, by contrast, was a textbook case of expulsion or ethnic cleansing, combined with a mutual war. There were many massacres and gang-rape was weaponised to get civilians to flee. But unlike the Shoah, which flickered out, the Nakba festered.

We are now at a historical crossroads. Another Nakba has already been committed in Gaza, although it is still possible that surviving expelled populations will be returned “home”, at least nominally, to the place where they used to live and which will need to be rebuilt. However, there is also a second scenario that points towards the possibility of genocide. This is a worry for everyone concerned, including many Jews.

The term “genocide” has been used in various media to describe both the horrible events of Oct.7, and the subsequent mass-killings in Gaza, but the term’s legal meaning, used notably by the ICJ in its ruling on a motion brought forward by South Africa, is controversial. Further, many different historical definitions exist, and it’s not only about huge numbers. A classical case is that of the Tasmanians, on an Australian island, with perhaps less than a thousand victims.

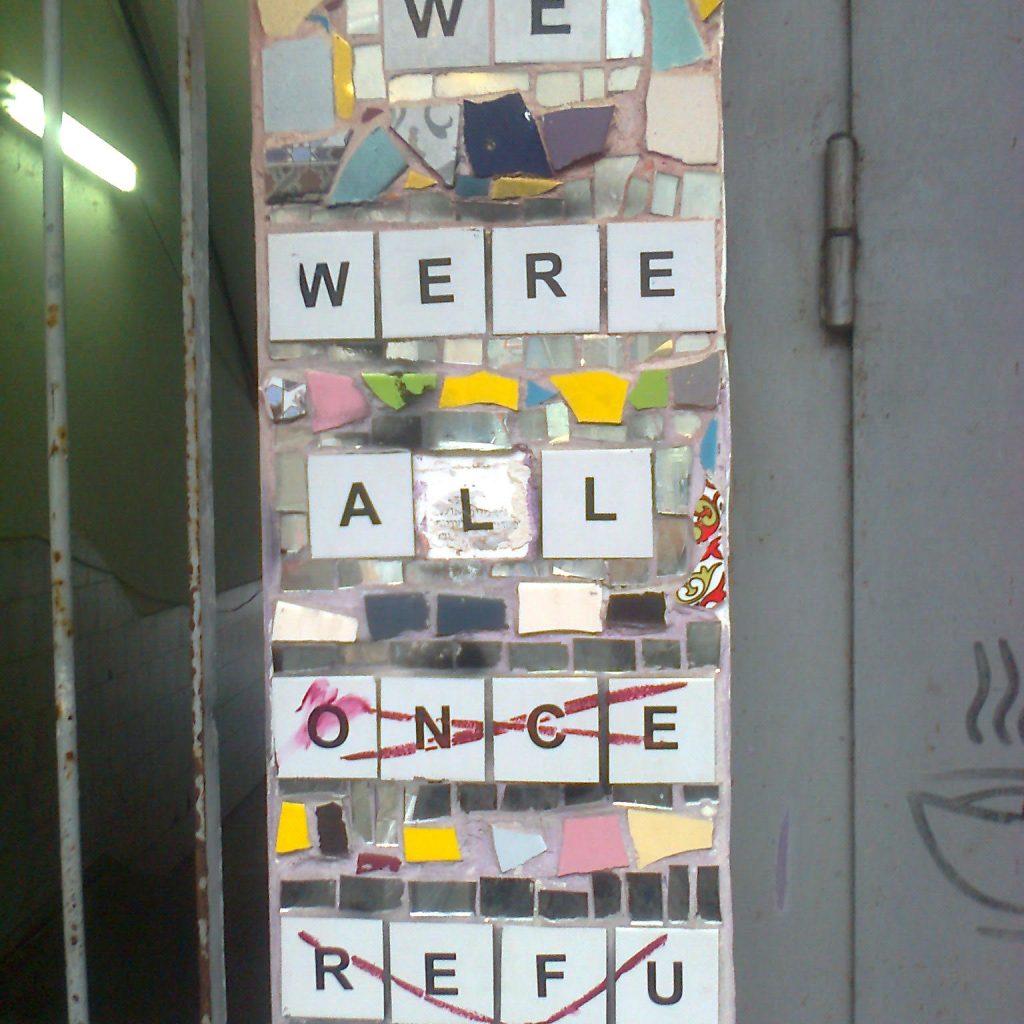

Is it possible that Zionism — as a self-defence and rescue effort — has gone volte face, and that the current events in Gaza and elsewhere will end up with some sort of “revenge genocide”? The level of Israeli emotional upheaval – while fully understandable in the case of the victims and their families – has reached such disproportionate dimensions, in some cases blind rage, that it beckons the question: What is its true source? Is this rather a misdirected payback for the Shoah – with eight decades of delay, and targeting the wrong people? Listening to many opportunistic references to the Shoah made by Israeli leaders, but also to the fears of regular Jews, it is clear that the Shoah still occupies centre stage in Jewish discourses and the collective subconscious.

Can you blame Israeli Jews for being traumatised for generations after the Shoah? Hardly. But having it out on the Palestinians, specifically Gazans, just does not do justice to anyone. Some argue that the tragedy of 7 October 2023 provoked or “justified” a genocide, but that is merely polemical and morally unconscionable. The highly unpopular Israeli prime minister, for example, has a long history of genocide denial, mass persecution, and even falsely blaming Palestinians for the Shoah. The numbers of Gazans who have so far been killed or murdered are higher than the official estimates, but not yet nearly approaching a six million mark. Then again, Israel is a smaller nation than Germany.

Judging from the pictures and footage, from eyewitness reports and the ongoing legal proceedings, the situation in Gaza has been described by Masha Gessen as a “ghetto liquidation” — except there is no death camp operating. There may not be need for one, as famine, dehydration, epidemics, lack of basic medical care, and vigilante violence may suffice to kill off many or eventually most Gazans. After US Vice-President Kamala Harris “studied the maps” and discovered that there was, indeed, nowhere to go for 1.5 or so million “folks” from Rafah, a fork on the road ahead emerged. But this time the “folks” are 2020s Palestinians, rather than 1940s Jews.

Perhaps the trauma of the Shoah is too great to be suppressed. Postwar Germany’s “reparations” could not really pay for the blood spilled. Zionism might be sucked back into the past. It could abandon any hope of a sustainable state solution, once represented for many by the 1990s Oslo Accords, in favour of a genocidal act.

Comment (0)