By Miri –

In recent years, critical positions towards the State of Israel have been increasingly delegitimised on the grounds of supposed anti-Semitic undertones. At the same time however, much criticism supposedly launched exclusively against the Jewish state and its supporters, did actually rest on a false understanding of what Zionism is and frequently conflated it with Judaism, as if the terms could be used interchangeably. The confusion of those terms is a dangerous one, as it actually does infer generalisations about Judaism as a belief system, as well as a culture and about the Jewish people as a whole and it therefore clearly does constitute an anti-Semitic position.

In recent years, critical positions towards the State of Israel have been increasingly delegitimised on the grounds of supposed anti-Semitic undertones. At the same time however, much criticism supposedly launched exclusively against the Jewish state and its supporters, did actually rest on a false understanding of what Zionism is and frequently conflated it with Judaism, as if the terms could be used interchangeably. The confusion of those terms is a dangerous one, as it actually does infer generalisations about Judaism as a belief system, as well as a culture and about the Jewish people as a whole and it therefore clearly does constitute an anti-Semitic position.

Particularly within the realm of social media, one of the few platforms, where anti-Zionist and/or pro-Palestinian positions appear to be flourishing, there is a growing need for a more reflected use of the terms in question. One way of countering the equation of Zionism with Judaism, or Zionists with Jews, is by highlighting those Jewish movements and ideas that were and continue to be opposed to the idea of a Jewish nation state.

In the following, we will introduce you to some of those ideas and their proponents. Obviously, due to the complexity and the variety of those positions, this list can hardly be exhaustive. A rough distinction will be made between those ideas that have a secular background, and those that are grounded in the Jewish scriptures. As usual, this distinction is a generalisation and the two streams are not always necessarily mutual exclusive.

Secular forms of Jewish Anti-Zionist Thoughts

The Bund

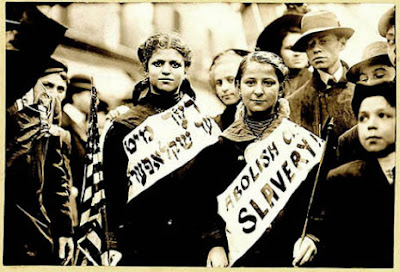

The General Jewish Labour Bund in Russia and Poland, founded in Vilnius in 1897, attempted to unite all Jewish workers in what was then the Russian Empire into one united socialist party.The Bund’s overall goal was twofold, on the one hand, it struggled for the cultural survival of the Jewish nation everywhere and to combine this with the universal class struggle for social emancipation and socialism. In order to achieve those goals the Bund allied itself with the Russian social democratic movement in their struggle to form a democratic and socialist Russia, within which Jews would be a a recognised legal minority.

|

| Abolish Child Slavery, written in English and Yiddish, NYC, May 1909 |

In its political outlook the Bund strongly opposed the increasingly popular idea of Zionism, viewing it as separatism and arguing that emigration to Palestine was a form of escapism. In its conceptualisation of Jewish nationhood the Bund focussed on Jewish culture, and especially the advocacy of the Yiddish language (as opposed to the revitalisation efforts of Hebrew by the Zionist movement). The Bund adopted the concept of national personal autonomy, which sought to “organise nations not in territorial bodies but in simple associations of persons”, thereby radically disjointing the nation from the territory.

After the Russian Revolution of 1917 it was precisely this propagation of national personal autonomy which stood in stark contradiction to the ideas of the Bolsheviks and Lenin, and the Communist Party eventually violently suppressed the Bund. Shortly after its foundation in Russia, however, Bundist groups began to constitute themselves internationally and their legacy continues in progressive and radical leftist Jewish groups until today. Remnants of the party remain active in Israel, as well as outside.

Jewish Anti-Zionist League

While most of the literature dealing with Jewish anti-Zionist attitudes focusses on an Eastern European, or Anglo-speaking context, and hence on movements by and large comprised of Ashkenazi Jews, it should be noted that also within the Sephardi communities, opposition towards the ideas of Zionism existed and continue to exist. Such is the case of the, admittedly short lived Jewish Anti-Zionist League in Egypt. As opposed to other movements, such as the Bund, the League’s main preoccupation was to fight the Zionist influence upon the Jewish communities in Egypt and to clarify to the Egyptian population that not all Jews were automatically Zionists. The League condemned Zionism as a tool for British imperialism and called for Arab-Jewish unity.

Due to its militant character and the agitations that it provoked in Cairo’s Jewish neighbourhoods, the League was officially banned by the Egyptian Ministry for Social Affairs for “reasons of public security” in 1947, after not merely two years of existence. Individual activists of the League reportedly continued their activities within different associations.

Jewish Anarchists

|

| The “Circle Aleph”, a play on the anarchist Circle A |

Apart from many individuals of Jewish origin, such as Emma Goldman and Alexander Berkman, who played key roles in the history of anarchism, there have also been a number of specifically Jewish anarchist movements, many of which were opposed to the ideas of Zionism. Yet, especially in the case of Jewish anarchists of the early 20th century, who witnessed a dramatic increase in anti-Semitic sentiments and actions, the perceived urgency to find a solution to the question of Jewish national identity led many to transgress at least to some extent the boundaries of anarchist dogma and its opposition to all forms of nationalism.

Today, one of the Jewish groups that probably receives most media attention, notwithstanding its small number, is that of the Anarchists Against the Wall, a group of Jewish/Israeli activists who support Palestinian grassroots movements in their struggle against the Occupation.

Religious Jewish Anti-Zionism

At least in its early history, Zionism was an idea advocated almost exclusively by secular Jews. Yet, as many Ultra-Orthodox anti-Zionists claim, Zionism is not only to be opposed because of the fact that many of its adherents are non-practising Jews or even anti-religious, but because Zionism’s fundamental principles are in conflict with the Torah.

To many Orthodox Jews the most basic of these conflicts goes back to the Three Oaths. According to the Torah, the present exile of the Jewish people from Israel is a consequence of their sins and therefore divinely decreed. Being bound by the Three Oaths, Jewish people are 1) not to ascend to Eretz Yisrael (the land of Israel) as a group using force; 2) not to rebel against the nations of the world; and 3) that the nations of the world would not persecute the nation of Israel excessively. The Jewish people are therefore neither commanded nor permitted to conquer or rule the Holy Land before the coming of the Messiah. As such the very existence of the State of Israel constitutes an act of blasphemy.

After the Holocaust and the subsequent foundation of the State of Israel, the relationship between many Haredi communities and Zionism became more complex, and some groups, such as the World Agudath Israel, originally one of the first Jewish Orthodox anti-Zionist movements, adopted a more pragmatic position towards the state.

There are however numerous Jewish movements, groups and organisations, both in Israel and beyond, who continue to consider Zionism a form of heresy, most notably among them are the Satmar Hasidim and Neturei Karta. Those living within Israel refuse to pay taxes and avoid obtaining any benefits from the state and basically live their lives as self-contained communities with few formal ties to the surrounding political infrastructure.

A small branch of Neturei Karta, however, took steps to openly condemn Israel by participating in demonstrations and by publicly supporting movements, parties and regimes opposed to Israel and Zionism. The same faction made headlines when some of its members participated in the infamous Tehran Holocaust Conference in December 2006. Although the participants did not deny the Holocaust or its extent, but rather condemned it being used as a tool for the oppression of other people, their very participation in an event that included a great number of notorious Holocaust deniers, was harshly criticised including from within their own ranks.

As already noted in the beginning of this article, there are many more critical positions towards Zionism coming from self-identifying Jewish points of view, including non-Zionism, post-Zionism and many more.

The very existence of a whole variety of Jewish stances that do not concur with that of the Israeli state and its supporters should suffice to reconsider one’s usage of the terms Zionism and Judaism and especially the connection between the two. These days some of the most fervent Zionists are not Jews, while some of the most ardent anti-Zionists are.

Comment (0)