– by Fred Schlomka – 19/2/2023

During February and March 2023, Green Olive Managing Partner Fred Schlomka cycled across part of the the Middle East, through a region marked by division, segregation, and political tension. His journey crosses many regional boundaries and borders that reflect a tense history. Fred’s observations and reflections are a snapshot of the region during his trip. Here are his daily dispatches and reflections from the field:

Day 8

Journey: Alsira – Jordan Border – Sinai

Distance: 15 km (10 miles)

Total Cycled: 359 km (225 miles)

For those of you who have been following my posts for this trip, you’ll notice that the title no longer mentions Saudi Arabia but Egypt – Today ends in the Sinai. More on this in a bit.

I depart at about 7:30 with the bicycle loaded in a van for the trip to the Eilat/Aqaba border to Jordan. I’ve cycled the Negev and Arava deserts in the past and have no desire to do it again. I spend the couple of hours reflecting on the past two days. My wife has criticised me for not mentioning the abuse of women in the various communities I have travelled through, going so far as telling me that my writing is often indicative of a – ‘white privileged male’ -. I defer to her greater wisdom.

So – to redeem myself – Yes, many of the women of Israel and Palestine are used and abused in the most horrific ways.

I could have written about the white slave markets of Tel Aviv where poor women from eastern Europe and Russia are enticed by promises of jobs and then on arrival are raped and forced into prostitution, and often sold on to other Middle Eastern countries.

I could have written about the increase in so-called honour killings in Israel, whereby misguided and brutal men will kill their sisters, mothers, cousins and aunts for perceived infractions of modesty or alleged or actual fornication outside of marriage.

I could have written about the Haredi women of Israel and beyond who are enveloped by their cultish religious sects, with many of them forced into child marriages, sexually abused, forced to work both outside and inside the home while their husbands pray all day.

I could have written about some of the women of the Palestinian villages and the Beduin women who are similarly oppressed by their culture, and forced to fit in with their mens’ notions of a proper chattel woman – often used and abused.

But I didn’t.

Instead I mentioned Zohar, Mirvate, Daphna, and Roseanne – all of them examples of emancipated women within patriarchal Israel and Palestine. a University professor in Haifa, a proprietor of a guest house in Beit Sahour (Bethlehem), a high school teacher in Tel Aviv and an urbane and talented city lady who chose to live in a West Bank village. All of these women beat the odds and became fiercely independent, each in their own way – also marrying and raising families.

One thing I have learned on this trip is that social emancipation can often be independent of political oppression, and societies can free women in sometimes unexpected ways. For instance Roseanne now lives within a traditional Palestinian social fabric in the West Bank and as such is expected to behave in certain ways. However she is a city lady and misses Amman. She explained to me that there she can breathe freely and has most of the social freedoms of a woman in western cities – despite the Jordanian regime being is many ways more politically oppressive and undemocratic than the Zionist state.

In most of my writing I do not go deep into a critique these social issues mainly because my focus is usually political and cultural. But my dear Sunita – point taken.

Back to the trip. After a 2-hour drive down the Negev and Arava deserts, I am dropped off at the Eilat/Aqaba border to Jordan and informed by the Israeli passport control that Israelis are not allowed to take bicycles into Jordan. This wasn’t the case when I last crossed this border with a bike in 2016. Apparently the rules changed about 5 years ago. That will teach me not to check on current protocols before a trip.

Anyway I tell the Israeli police that I will enter Jordan on my UK passport and they say that will be OK. – Wrong –

At first the Jordanian process seemed normal, until they asked me for my exit ticket from Israel. Instead of stamping passports, for many years Israel has provided a piece of paper on entry and exit. What I didn’t know was at that at the Aqaba border Israel gives a blue ticket to Israelis and a pink ticket to everyone else. So despite my UK passport, the Jordanians immediately knew I was Israeli.

Long story short (it took hours), after an attempted intervention by my friend Laura in Amman who runs a tour agency, the Jordanians denied me entry and I had to return to Israel. More correctly they denied my bicycle and told me if I left the bike in Israel then I would be welcome. I was certainly not about to leave the bicycle in Israel so I decide to forfeit going to Saudi Arabia for now. Time for plan ‘B’. The Sinai is nearby.

After returning through the Israeli border formalities. I cycle through Eilat quickly. I really do not like the place. It is kind of like Israel’s version of Las Vegas by the sea. Apart from a stop for lunch I quickly arrive at the Taba border to Sinai. More chaos. I get through the Israeli controls fairly quickly but on the Egyptian side there are issues. Here we go again.

At first I thought it might be more of the same kind of rules as Jordan, except this time the Israelis gave me a pink slip, as they do at the airport. I guess there’s a deal with Jordan to differential Israelis for Jordanian border police convenience. So when the Egyptians ask where I am from I say ‘Scotland’. That’s always a good one, since apart from being true, everyone loves the Scots. On policeman mimics the bagpipes. Helps to break the ice. However the bike is suspect.

At the security counter, all my bags once again go through a scanner but nothing is actually opened, except my tool kit. Then when emptying my pockets I realise I left my Israeli passport in a trouser pocket, so I nervously leave it there while emptying everything else in my pockets. I am patted down by a young policeman who seems a bit nervous since his boss is watching. I make distracting jokes during the process and although I feel his fingers touch the passport he does not take it out of the pocket. Whew!! They need to train their cops better.

Then the policeman’s plain clothed boss struts over. and carefully photographs the bicycle. I try to chat with him while he does this but am ignored. Then after they are satisfied, with a personal police escort, I am shepherded through the passport control with the bike, and then to a building off to the side. Uh oh, I think. This is the same building Sunita and I had to visit during the one time that we brought our Israeli car to the Sinai. Never again. It took hours. This time, surely they are not treating the bicycle like a car with attendant security deposit and the requirement to ‘rent’ the Egyptian number plates.

The policeman escorts me and the bike to a counter inside the building. The gentleman behind the counter looks much more sophisticated than any of the policemen I have been dealing with, most of whom are conscripts. The official comes out of his office and peers at the bike. I can tell from his expression that he also thinks it is a bit ridiculous that I have been brought to him. Slightly embarrassed he asks how much the bike is worth. Now this bicycle was custom built for me and I have since added lots of bells and whistles to make it a comfortable touring bike. I make a quick decision and tell him a number that is a fraction of its real cost.

He is satisfied and proceeds to write something in Arabic above my entry stamp, and tells me to come to him first on my return, and he will verify on the passport that I am taking the bicycle out of the country. Fair enough. I guess they don’t want me selling it and returning empty handed. Then I am done – or so I thought.

At the gate exiting the border facility the guard barks at me asking for a receipt. Since no-one asked me for money I have no receipt. He sends me back to the terminal and I am told to change money, a precise amount, $15 = 450 Lira. I change the money and return to the gate. He again asked for a receipt. I tell him no-one gave me a receipt. Then it dawns on me that he actually wants the piece of paper I was given by the fellow who stamped the passport. I show it and he rolls his eyes at the stupid foreigner. I explain that it is more proper to refer to the paper as a ‘ticket’ since a receipt is only given in a financial transaction. He laughs.

So I exit the facility and proceed to start cycling south. I get maybe 20 metres when policemen rush out of a hut and start yelling at me. I stop. The boss policeman tells me that bicycles with foreigners are not permitted to cycle in Sinai, especially on this road. I show him the passport where the official wrote in details about the bike and the officer said it was not relevant since his department controls the roads and no bicycles are allowed. I ask if he ever talks to the police department at the border control to make them aware of regulations and he says it is not necessary so they never talk. OK.

I am allowed to put the bike in a taxi/van so I ignore all the taxi drivers vying for my trade, and proceed to research beach camps along the coast, and also send a message to my daughter Maya who goes to a Sinai camp once or twice a year. I telephone the Sakrah Tah beach camp just 26 kilometres along the coast. Perfect. I select a driver who is the least annoying and ask the price for a private trip in his van to the camp. 100 shekels he says, about $30. I call the camp again and they say that’s the correct price. So we pack the bike and gear in the van and off we go.

I should probably mention that the only women I dealt with at all these borders were Israeli. The Jordanian and Egyptian officials and police were all men, a reflection of deep cultural differences.

The camp is perfect. I am greeted by the owners, Basant & Achmad, and made very welcome. The best part is that there are no other paying guests at this time. I am shown to my hut near the water and spend a pleasant evening with the owners and their friends. Upon hearing about my day, Achmad tells me that there are ferries to Aqaba and perhaps I would have better luck arriving from Egypt with my UK passport than from Israel. I mull this over, am tempted, but finally decide that I have have had enough hassles for a while and don’t want to risk it.

Basant and Achmad are from Cairo. They established the camp to get away from the pressure of the big city. I ask Basant if they bought the beachfront property or rent it. I am surprised when they say it belongs to the government and they have no permission to have the camp. Essentially they are squatters. However local Bedouin tribes control a great deal of the activity along the coast so they pay a Bedouin tribe some ‘rent’, essentially protection money although they do not call it that. They also explain that although the heavy police presence and frequent checkpoints is a hassle, it keeps them safe, as do the Bedouin. I’m told there is no crime along the coast, and the mafia-style Bedouin gangs and Ansar Bayt al-Maqdis (Islamic State) who control some of the Sinai interior stay away from the east coast. These groups make money through extortion, slave trafficking, drugs and gun smuggling.

I start to see my Sinai detour as a gift of time. Instead of touring in Saudi Arabia, I can now spend some time writing – not daily logs such as the one you are reading, but a book project that has been started but a bit neglected this past winter. I have hundreds of blog posts from my travels – hundreds of thousands of words. A few months ago I started collating them and editing some in preparation for a book. Plus I also need to write more, to fill in some of the gaps and early travels, before I started writing seriously. It is a huge project.

This will be my last post on this trip. I will spend the time on the beach in Sinai, reflecting and writing. So from this peaceful and beautiful spot I bid you all farewell for now. Keep commenting and do send me private messages if desired. Shalom/Salaam till later.

Day 7

Journey: Beit Ummar – Alsira

Distance: 43 km (27 miles)

Total Cycled: 344 km (215 miles)

As planned, abu Yusef showed up with his van at 8am and we loaded up the bike and gear. Yesterday’s mishap with the electrical assist means that going forward, I will be cycling with leg power only. Since I had calculated today’s distance based on having electric assist, I thought it better to be driven part of the way. The kilometres detailed above are the cycling distances only.

I say goodbye to Mousa and his lovely family, and we trundle off heading south past Hebron. I send a text to my Green Olive colleague Erez to see who his contacts are in al Tuwani in case I want to visit the Palestinian village en route to the Negev. He replies that he is on the road to nearby Um Al Khair as a volunteer for their work day. So I change plans and decide to make a stop at the village to meet Erez and the group.

We pass the Karmei Tzur settlement. All is quiet. The landscape is stunning with terraced hillsides, olive trees, almond blossoms, grape vines and much more to feast the eyes on. We pass Hebron and the all-Jewish suburban settlement of Kiryat Arba, where they have a memorial and still celebrate the anniversary of Baruch Goldstein’s death. A few decades ago, Goldstein slaughtered dozens of worshipers with a machine gun in the Mosque at Abraham’s Tomb in Hebron. To many settlers he remains a hero.

We are well passt Hebron and abu Yusef drops me off at the side of the road, waits until the bike is ready to roll, then I wave him off. It feels odd to be cycling again without electric-assist, but my legs are strong and I soon settle into the cadence of the road. The turn-off leading to the village of Um Al Khair is right next to the perimeter wall of the Carmel settlement. These local settler Israelis are notorious for harassing and attacking their Palestinian neighbours, including children on their way to school. Israeli and foreign volunteers often stay in the village and accompany the children to school as human shields against the settlers and Israeli military.

The village of Um Al Khair is a rough and ready affair. The residents are of Bedouin extraction and have long been settled. They mostly herd goats and are day labourers. The village existed long before Israel conquered and occupied the West Bank, yet the village has been granted no legal status by the state. They are a simple people. A noble and proud people. Salt of the earth – yet one of the most powerful countries in the world sees fit to oppress them and deny them basic human rights. Why? Because they are not Jewish.

Erez arrives with his work group and they are briefed on the day’s activities. I socialise a bit then it is time for me to go. I cruise back to route 356, the main road south, and before long arrive at the settlement of Sousya, notorious for harassing their Palestinian neighbours. Since I haven’t had breakfast, I decide to see if there is a cafe or small shop, so I follow a car through the security gate (no guard) and find the village shop. As I chomp on a breakfast of hummos and orange juice, a kippa-wearing young man wanders over and starts a conversation. He is in his mid-twenties with the religious identifiers of long sidelocks and tsit-tsit (knotted string) poking out of his trousers. We chat. I ask why he lives there.

He was raised on the settlement. Knows no other life. Waxes almost poetic about a life with fellow believers, and seems entirely ignorant about the state and the larger world. Basically his community for the most part functions like a cloistered cult. Everyone is ‘against’ them – The Arabs – The State – The Leftists. No rational discussion is possible so I leave before I say something that might identify me as an enemy.

The checkpoint to exit the West Bank is just a few kilometres south. Much to my surprise I pass without being stopped. The guards smile and yell ‘kol ha kavod’ (Good for you). They are obviously impressed by my bike loaded with baggage. Soon I am on the long descent from the hills to the Negev Desert. The ride is exhilarating. It is a drop of almost 600 metres (1,800 feet) over about 3 kilometres. This leads to route 31 and I head west for about 10 kilometres before turning off to the unrecognised Bedouin village of Alsira where my old friend Khalil lives.

We go back about 15 years. Khalil is an impressive man. He was a high school teacher and gained a law degree studying part time while still teaching. Now retired, he devotes himself to his family, uses his knowledge of law to help his people, touring delegations, and hosting guests at his home. His village is on the itinerary of Green Olive’s ‘Bedouin Reality Tour’, and I remember the days when I used to guide the tour more than ten years ago and learned from Khalil most of what I know about Israel’s oppression of his ancient people.

Dinner is festive with a gaggle of Israeli/French immigrants and a couple with a child. The food is great, and the conversation naturally steers towards politics. The Israeli guests consider themselves to be quite liberal, after all here they are in a remote Bedouin unrecognised village. However when Khalil mentions the ‘A’ word (apartheid) they are shocked and I go to great lengths to explain that we have a sort of ‘Grand Apartheid’ in the West Bank and ‘small Apartheid’ in Israel – pointing out the Bedouin lack of rights compared with their Jewish neighbours. They aren’t convinced since as good Zionists they firmly believe that the ‘Jewish Homeland’ must be ruled by Jews, and like many liberal Zionists they tend to ignore the dichotomy between their supposedly liberal democratic values and their Zionist ideology.

Anyway we part friends and certainly Khalil and I have given them food for thought. I retire to my cosy room and sleep.

Day 6

Journey: Beit Sahour – Beit Ummar

Distance: 17 km (11 miles)

Total Cycled: 301 km (181 miles)

Today doesn’t exactly go as planned, but then, that’s part of the excitement of adventure travel. More on this later.

I depart early and say goodbye to Mirvate after a sumptuous breakfast. The original plan had been to visit my old friend Bruce in Tekoa, but since the Israeli military saw fit to invade the old city of Nablus yesterday during the busiest time of day, killing 11 people and injuring over 100, a general strike has been called for today, and the shabab could well be on the roads by mid morning hurling rocks and confronting settlers and the IDF, inviting lethal retaliation. I thought it best to avoid this and leave before they were out and about.

So off I go south into Gush Etzion and soon am passing Herodion, the 2,000 year-old summer palace in the Judean Hills that used to belong to King Herod, of biblical fame.

I pass the Jewish village of Tekoa (a settlement) and continue up the hill. The landscape is stunning but I can’t really appreciate it since the hills are gruelling, really gruelling, even with my electro-assist drivetrain. Then the bike begins to stutter, with the power going off and on in quick succession. At first I think it is the battery connection, and tighten the ‘goomy’ (heavy elastic strap) that binds the battery to the connecting plug. At first it seems to be working.

Then the stuttering again. I tighten the elastic even more – and broke off the key inside the battery. Oops! The battery still seems to work but the motor is not going. I switch batteries and still can’t get the motor to work. It has been grinding a bit on the steep hills and I am afraid it might be burnt out.

I push the heavy bike up the remainder of the hill to a shop opposite an IDF outpost. I am in the middle of the Arab village of Tekoa, and give the situation, maybe not the best place to be. However The shopkeeper is friendly so I park the bike and tinker with it. Hopefully the local resistance will not decide to harass the IDF mini-fortress while I am there.

I finally give up and call my friend and colleague Mousa in Beit Ummar and request a rescue. He arrives 30 minutes later in a van, We load up the bike and baggage, and speed off to Beit Ummar passing the upper middle class Israeli settlement of Efrat. Mousa points out the rapidly expanding new neighbourhoods, eating up confiscated Palestinian farmland. Cranes and roadworks are everywhere.

Then as we come closer to Beit Ummar I see a massive road project that has begun since I was last there. Apparently a bypass road is being built to the southern settlements, around Beit Ummar and other Palestinian villages, in much the same way that route 443 was built north of Jerusalem. This will be another segregated ‘Apartheid’ road with limited access for Palestinians and servicing the southern settlements.

After arriving at his house I meet Mousa’s new wife Roseanne and their beautiful infant son Forat. The bicycle ‘mechanic’ arrives soon after, but is not equipped to fix my machine. We both fiddle a bit and conclude that the motor is indeed not working. Probably there would be a bike shop in Jerusalem that could help, but a new hub motor would mean rebuilding the front wheel. Could take days.

Decision time! I decide to leave both batteries and chargers with Mousa and continue ‘old school’ and use only my muscle power to continue the trip. Not what I planned, but not the end of the world. I would figure out later how to get the batteries back to Jaffa. Problem solved.

Mousa and I first met about fifteen years ago on an olive tree planting exercise to try and ward off more land confiscations by the nearby settlement of Bat Ayin. The Israeli army showed up and declared the ground under our feet to be a ‘closed military zone’ and promptly detained our group. The other Israelis were told to go home. The Palestinians were arrested as was I, because of the Swiss Army knife in my pocket. I was interrogated about why I was carrying a ‘weapon’. There’s nothing like getting arrested during a political action for people to bond. Mousa and I have been firm friends ever since.

We drive over to Mousa’s office at the Centre of Freedom & Justice (CFJ) and meet his new General Manager Khaled Abu Awad, whom I knew as the founder of Roots, an organisation that brings together Palestinians and Israelis for learning and dialogue. Mousa founded CFJ over a decade ago and although their initial focus was on non-violent resistance activities, more recently they have developed cultural and economic development projects at ‘The Park’, as it’s known. The centerpiece is 1,400 year-old olive tree!!

A family from Manchester shows up and we all get a tour of the extensive facility that Mousa and CFJ have developed. There’s a swimming pool, football pitch, outdoor gym, huge hall used for weddings and activities, picnic tables, a restaurant, and a hostel being built. The place is kind of like a cross between a theme park and a community centre. I am impressed.

So Mousa and I talk a little business. Green Olive Tours already sends our clients to stay at his hostel as part of some of our package tours. We can probably ramp this up a bit I tell him, and perhaps solicit for volunteers to help with their childrens’ summer camp.

Back at his home a lovely vegan meal is served and I bed down for the night.

Day 5

Journey: Jerusalem – Beit Sahour

Distance: 19 km (12 miles)

Total Cycled: 273 km (170 miles)

Easy cycling day today, as planned. I spend the morning at the Jerusalem Hotel for two business meetings, then check out and hit the road. I opt to cycle around the Old City via the two-lane tunnel road under New Gate. When there is no shoulder on the road, I take up a whole lane for safety. It’s odd, but car drivers still get annoyed with the bicycle even when the road is congested and I am easily maintaining the same speed as the cars. I think their egos get offended when a bicycle gets in front of their car, regardless of whether traffic is being held up as a result, which in this case it is not.

I emerge from the tunnel just past Jaffa Gate, and cruise up the hill to Hebron Road, the main drag out of the city to the south. Soon I am zipping past some lovely old Ottoman era homes and mansions which were confiscated post 1948 when the middle class Palestinian Arab civilians fled the war and were never allowed to return. Many of the homes were squatted in by new Jewish immigrants, or ‘allocated’ to government officials, who subsequently gained title to the properties under Israel’s odd legal code.

I pass an open piece of land purchased decades ago by the US Government, originally planned as the site of a new Embassy, it is now surrounded by high-rise buildings which would be a security risk. So the new embassy is being built elsewhere. Then an old Jordanian border pillbox comes into view. This was the beginning of no-man’s land between 1948 and 1967 when the Jordanians were administering (or occupying?) the West Bank. Th pillbox new sits incongruously in front of soaring high rise apartment buildings.

Once through no-man’s land (perhaps women were allowed), I am on territory annexed to Israel in the Aftermath of the six-day war in 1967. Along with most of the rest of the world, the US did not recognise the annexation until ex-Prez Trump decided to cosy up to Bibi and move the US Embassy to Jerusalem. Mar Elias Monastery looks a shadow if its former self with huge infrastructure work around it, preparing the next section of the Jerusalem Ring Road on land confiscated from the venerable institution.

Rather than turn left down towards my destination, I continue to the ‘300 Checkpoint’ to check out the situation there. The actual checkpoint is a gap in the 8-metre wall (24 feet) that surrounds Bethlehem to the north and west. Most of the rest of Bethlehem has fencing to block off the city from the surrounding area which is fast being used for Israeli settlement building, thwarting any expansion of the city of Jesus’ birth.

Rachel’s Tomb, Which is in Bethlehem, has been gerrymandered into Jerusalem by the Israelis by bending and twisting the huge wall to entirely block off any access from Bethlehem. the situation surrounding Rachel’s Tomb has an architechtural Kafaesque quality to it. This is further illustrated when I cycle up to the gate and ask the guard if I can pass to see the Tomb. “No bicycles allowed”, he says in Hebrew. “You can leave the bike here and walk”. This is said while he stands underneath a sign which clearly states that private vehicles are allowed, but no pedestrians. I point this out to him in my lousy Hebrew but he will not budge. Such is the petty power of a minimum wage guard with a gun.

I retreat and retrace my route until the turnoff to the Har Homa settlement, a towering fortress on the hill below. I remember one of my first acts of protest in Israel 20+ years ago was to participate in a demonstration against the breaking of ground for this neighborhood. It is now home to over 30,000 people on 1,850 dunams (about 462 acres) of land Israel expropriated from Palestinians in 1991.

The cruise down the steep hill is breathtaking and the bicycle reaches 60 km/hour. A bit too fast considering the load I am carrying, but I couldn’t resist. Har Homa sweeps past and soon I am through the checkpoint and in the West Bank ‘proper’. Upon making the left turn to Beit Sahour, I pass the red sign warning me of the danger of visiting my friends there. After a grueling ride up a very very steep hill, I make a right at the YMCA and arrive at Mirvate’s home. She runs a B&B and is a Partner of the Green Olive Collective.

After settling in, a cup of tea, and a bit of play with Mirvate’s gorgeous grandaughter Melina, I head out into town and visit some old friends. It’s good to be here. Later back at Mirvate’s house we are picked up by another Partner, Yamen, and head over to the Olive Grove restaurant for the first ‘in-person’ Green Olive Partner’s meeting for at least a year. It was good to catch up and discuss some business items.

I sleep well, totally exhausted from the day.

Day 4

Journey: Modi’in – Jerusalem

Distance: 36 km (22 miles)

Total Cycled: 254 km (158 miles)

I depart Modi’in early and turn on to route 443 at the southern edge of town. The Green Line is just a few hundred meters ahead, with the checkpoint flanked by walls and rolls of barbed wire. Beyond is the West Bank, conquered in 1967 and the subject of extreme controversy every since. If the Golan Heights and East Jerusalem are included, almost one million Jewish Israelis – the Settlers – now live on conquered territory in defiance of international law. Israel’s new ultra-nationalist government is poised to increase that number exponentially over the coming years.

I plow on past the checkpoint. There’s no control on entering the West Bank, only on leaving. A side road is immediately after the checkpoint, leading to the Palestinian village of Bayt Sira of the al-Bireh Governorate. There is a secondary checkpoint on the side road, and a red sign warning that “Entrance for Israelis is dangerous.”

Route 443 is mostly uphill, leading to the Judean mountains where Jerusalem perches on top. It is a 4-lane highway, and sometimes called an Apartheid road since it was build as an alternate route for Israelis to access the settlements and reach Jerusalem from Tel Aviv. Two Palestinian roads go under the highway without any access. Two other Palestinian roads have entrance points to the highway, with checkpoints of course. Originally it was 100% impossible for Palestinians to access the road. Then the Israeli high court decreed that some access was essential, so the present system was put in place. In practice almost no Palestinian traffic uses the road. I certainly have never seen any. An apartheid road.

Route 433 is an important part of the Israeli occupation infrastructure and used to limit Palestinian freedom of movement, supposedly for Israeli’s security but it is part of the longstanding plan (The Alon Plan) to restrict Palestinians to ever smaller areas of the West Bank, much like the Americans restricted the natives to ever smaller reservations while their land was being settled by foreign immigrants.

Twenty years ago when I was Operations Manager for the Israeli Committee Against House Demolitions (ICAHD) I used to drive the road daily from Kfar Saba to Jerusalem. At the height of the 2nd Intifada, Palestinian snipers used to occasionally shoot at cars on the road, so I got myself a bullet-proof vest and steel helmet and drove the route at an excessive speed. The police were not inclined to give out tickets on route 443 at the time.

Now I am seeing the landscape at a more leisurely pace. Between the fencing along the road, ancient olive groves can be seen on narrow terraces on impossibly steep slopes. Villages are on the higher slopes. Almond trees are in full blossom giving the rather stark landscape a seasonal frill.

It’s a cloudy day with a mild temperature. Good for cycling. I arrive at the only petrol station on the road – a lifeline for the adjacent fenced off Palestinian village. The petrol company employs many of the villagers who have a special gate to access the petrol station during working hours.

I stop at the ‘Expresso Bar’ for a work session and find half a dozen Israelis having a shouting match regarding the judicial reforms that the government is pushing through. In typical Israeli fashion they yell and scream their opinions, then depart as good friends. Of course this type of friendly argument is fading in Israel as a chasm has opened between religious ultra-nationalists and the mainstream.

I chat a little politics with Avi the cafe owner. He describes himself as ‘leftist’ but in true Zionist fashion, completely negates any possibility that his Arab neighbours here in the occupied territories could ever be politically equal, or should be extended the same freedoms as Israeli Jews. A Zionist Leftist in Israel would be considered pretty far right in Europe or the USA, yet are considered traitors by supporters of the current government – a good indicator of the current political spectrum, and where it is heading.

I continue and pass the settlement fortress of Beit Horon. Parallel to the road the perimeter wall of the Jewish village soars upwards for about ten meters (30 feet) and is topped by rolls of razor wire. Within the walls an upper middle class Jewish Community lives with every modern convenience including a resort hotel with a swimming pool. Less than one kilometre away are the Palestinian villages of Tira and Beit Ur al-Fauqa where the Arab population ekes out a living as if they were in a developing country instead of the so-called ‘Start-up Nation’. Such is racism. Such is apartheid.

I continue to the massive checkpoint at the entrance of the Jerusalem suburbs – still deep in the West Bank – and am permitted to enter without being inspected with a cheery wave by the heavily armed teenage soldier. Wall loom as the road navigates between the notorious Ofer prison and the various walled-off Palestinian suburbs of Jerusalem. I opt to enter the city via Atarot and Qalandia, the main checkpoint to Ramallah. There is a huge amount of construction on the Jerusalem side of the Qalandia Checkpoint. The Atarot industrial zone appears to be getting expanded, giving Israeli companies easy access to cheap Palestinian labour on the other side of the wall. Special permits are available to the ‘lucky’ Arabs who manage to land a job in the zone. There is also an ultra-orthodox neighbourhood planned for the derelict Atarot Airport.

I cycle down the road from Qalandia Checkpoint next to the Wall that divides the Ar-Ram neighbourhood, and continue into Beit Hanina, possibly the most ‘normal’ and middle class Arab community in Jerusalem. They are Jerusalem residents and many have applied for, and received, Israeli citizenship.

I have to be nimble on the busy neighbourhood roads. Beit Hanina has some cycle paths but they usually end abruptly and often have cars parked on them. So I opt to cycle on the road, ramping up my speed to match the cars, in order to stay safe. I come to the massive and very busy intersection at French Hill, the first east Jerusalem settlement to be built after 1967. This is the only traffic light on Route 1, between Tel Aviv and the Dead Sea. Eventually a cloverleaf and tunnel will be built, eliminating the traffic lights.

Finally I arrive at the Jerusalem Hotel near the Old City’s Damascus Gate. It’s a classic old Palestinian hotel with friendly staff, good food, and great rooms. Green Olive Tours books clients into the hotel, starts some of our tours here, and give briefings in the café.

The rest of the day is taken up with business meetings and an opportunity to stroll into the Old City and visit friends.

Day 3

Journey: Hod HaSharon – Modi’in

Distance: 43 km (27 miles)

Total Cycled: 218 km (136 miles)

Hod HaSharon is now part of the greater Tel Aviv jumble of suburbs, absorbing formerly independent villages and towns. Many of them retain nominally separate local councils, but are joined at the hip in a continuous urban sprawl. I navigate carefully out of this symbol of demographic and economic growth. First I searched for a cycle route on Google maps. I’ve found generally that this doesn’t work but wanted to try again.

Sure enough, the route takes me first along the busy route 40, with lots of roadworks including new cycle lanes. I continue to be impressed by Israel’s commitment to dedicated cycle lanes in the cities and suburban towns. All the remains is to place cycleways next to the intercity highways like they have in the Netherlands.

Google Maps takes me off on a side road to the ‘Baptist village’, ending in a muddy path that is only suitable for mountain bikes. There really needs to be another route symbol on Google maps, for road bikes and touring bikes. Anyway I am actually happy to see the Baptist Village. It brings back memories. The Village, near Petah Tikva, was founded in 1948 as a cooperative for Jewish believers in Jesus. The state of Israel frowns on proselytizing Christians so this new church facility charted a course that eventually made it an Israeli sport and culture institution, although converts are few and far between. However as a ‘recognized’ religion, they are allowed to rotate Baptist clergy from the USA through the facility on a quota basis, much the same as the Catholics and other large denominations. When my son Muki attended the American International School in Israel, he played some ‘away’ games of baseball at the Baptist Village. Memories . . .

I chart my own way to route 444 which runs closely along the Israel side of Green Line, paralleling the toll road, route 6. Along this route lie many of Israel’s settlements on both sides of the Green Line, including El’ad, Shoham, Beit Aryeh Ofarim and Modi’in Illit, attracting Israelis through cheap housing and subsidised mortgages – with the added advantage of being within a 30-minute drive to Tel Aviv in good traffic. Most of the residents of these outlying communities moved there for economic and lifestyle reasons, not politics, and most work in the greater Tel Aviv area.

I arrive at a wooded area at the beginning of route 443 with a caravan kiosk selling falafel. I have lunch and settle into a 2-hour work session on my laptop at a picnic bench. It is quite pleasant under a leafy canopy, but I could do without all the trash lying about – not uncommon in parks and public places in the countryside. Locals need to learn to pickup after themselves.

A few hills to ride over then Modi’in come into view – an ultramodern brand new city, with a high-speed rail link to Tel Aviv and Jerusalem. Planned in the 1970s as a new city in the hills, straddling the Green line, half way between Tel Aviv and Jerusalem, it became a popular place for working class Israelis to get up and out of the poor city neighbourhoods and become upwardly mobile. My cousin Rivka lives there, on the Israel side of the town. Married to Israel (yes that’s a personal name too), a scion of a Yemenite farming family from a moshav (cooperative village), they bought a house in Modi’in several decades ago, became moderately religious, and raised a fine family. It’s been a couple of years since I have seen them so this visit is much anticipated.

I navigate Modi’in successfully and arrive at Rivka’s home. My bicycle is safely locked in an outdoor shed, I shower and am ready for a family evening.

Her son Dolev and his family are also visiting, complete with their gorgeous young children. My daughter Maya arrives from Jaffa and a lively evening ensues, complete with a fine vegan dinner. We stay away from deep politics. No point. We have had all the debates and arguments over the years. The family is moderately right wing on the Israeli spectrum. In the USA or Europe their political view would be considered radical right wing. Such is the difference in the political spectrums.

We did touch lightly on the current issue of how to appoint Supreme Court Justices, and it was explained to me that ‘on Facebook’, there is a video where an Israeli lawyer ‘explains’ how judges are chosen for the high court, and why the process favours ‘the left’. I resolve to check this out.

I couldn’t find the FB video but I did find an authoritative source of information in the Israel Democracy Institute. Here’s what I found: Supreme Court Judges are appointed by the President of Israel, from names submitted by the Judicial Selection Committee, which is composed of nine members: three Supreme Court Judges (including the President of the Supreme Court), two cabinet ministers (one of them being the Minister of Justice), two Knesset members, and two representatives of the Israel Bar Association.

There is no ratification process of new Justices.

The present elected government of Israel wants to change the rules to allow the governing coalition a deciding voice in the selection of new Judges. They also want the power to disallow any Supreme Court decision through a simple majority vote of the Knesset.

I consider this to be move towards authoritarianism or worse – and unheard of in any democratic country. Of course as far a the Palestinians are concerted, this supposedly ‘leftist court’ has always rubber stamped their oppression and draconian security measures such as administrative detention without any due process.

For those of you who are interested, a full accounting and explanation can be found at the Israel Democracy Institute: https://en.idi.org.il/articles/46674.

The evening winds down. I am exhausted and sleep well.

Day 2

Journey: Atlit – Hod HaSharon

Distance: 83 km (52 miles)

Total Cycled: 175 km (109 miles)

I am up at the crack of dawn as usual and have a nice breakfast chat with Zohar. I miss these chats. It’s been almost a year since we’ve seen each other. Too long. Busy lives, Travelling, all take a toll on relationships. But I am happy to be here. Zohar heads off to her morning pilates, and I pack the bike and am off.

I decide to go straight over to route 4 and head south. It’s a straight run down the highway. The first section is interesting and I pass a cross-section of Israeli agricultural communities – kibbutzim and moshavim – formerly collectives and cooperatives, now undergone a capitalist conversion and morphed into the Israeli version of agribusiness.

Al-Furaydis looms ahead. In some ways a typical Palestinian Arab village in the north, but perhaps a bit more affluent due to it’s proximity to route 4, and the resultant access to Israeli traffic and customers. All kinds of businesses line the road, from hardware stores to plant nurseries, restaurants and bakeries. Despite the politics of the country, Jewish customers are valued and all the Arab businesses have Hebrew signs to help draw in the shekels.

I am reminded of the nearby Palestinian village of Tantura which was the site of a notorious massacre during the month that the state of Israel was declared, May 1948. The villagers had surrendered to the 33rd Battalion of the Alexandroni Brigade of the Hagana, the pre-state army of the nascent Jewish state. Somewhere between 100-200 unarmed people were subsequently slaughtered and placed in a common grave. The war crime was covered up and till today, there is no official record, only the results of private research and eye-witness accounts by some soldiers and village survivors. War is hell.

My original plan was to make a pit stop at the Poleg Industrial Zone near Netanya, and take in a karate class at the dojo, where just a year ago I was tested and awarded my 3rd Dan Black Belt. Unfortunately I misjudged the timing and couldn’t make the 08:30 class. Oh well. Another time.

The day becomes a bit monotonous as I pass strip malls and industrial areas, but I make good time. I telephone a bicycle shop in Ra’anana and they agree to do some quick repairs to my bicycle when I arrive. The brakes on the bike are a bit spongy and the battery connector needs replaced.

I lived in Ra’anana many years ago with my wife and kids when we arrived in Israel as landed immigrants. There was an immigrant hostel with free Hebrew lessons to make it easier to assimilate. We found an apartment within a few months, but despite our intent for Ra’anana to be a ‘soft landing’ for the kids (it was), the affluent English-speaking bourgeois culture was not really my cup of tea. Too many white people. So we moved to the next town of Kfar Saba, with its more heterogeneous demographic – although in recent years it too has become gentrified and expensive.

My old friend Dan is meeting me for lunch, but after arriving in Ra’anana, I head straight to ‘Ra’anana Bike’ on HaNegev street where I am attended to straight away. The bike is left there for a few hours and I get to stretch my legs. Dan awaits me with a bowl of miso soup for our first course at KOI ASIAN CUISINE. From there we go to a café for our second course of hummus and garbanzo beans. then some delicious tea at Caya Specialty Coffee – קפה קאיה.

I pick up the bike and depart after a rigorous test ride then some final tweeking. I am satisfied with the work, although they didn’t oil anything or wipe off the dirt from the road. However the price was fair, and in today’s very high costs in Israel, that’s a rarity.

Off to Daphna’s house in Hod HaSharon, an area that was once agricultural but now is full of upscale suburban homes and apartments in high rises. Daphna and I go way back thirty-five years and more. I haven’t seen her for ages. The house is a classic Israeli moshav house that belonged to her parents. They have passed on but Daphna and her siblings keep it on, and use it. The neighbourhood was once agricultural with a cooperative framework, now most of the area is gentrified with private upscale homes, but Daphna’s house remains a proud relic of a bygone era. We shmooze and go out for dinner. Then bed. I’m exhausted.

Day 1

Journey: Jaffa to Atlit

Distance: 92 km (58 miles)

After a couple of intense days helping staff the Green Olive booth at the Tel Aviv Tourism Expo, I am ready for a break. My intention is to cycle around Israel visiting friends and family, hold some business meetings, cross into Jordan and then Saudi Arabia.

It is about 9am on Shabbat as I cycle north from Jaffa along the promenade. It is already packed with joggers, cyclists and assorted others. This cross-section of Tel Aviv is the cutting edge of hip urban culture, enjoying a city seafront that rivals the best in the world. Cool bars and restaurants are in clusters next to the golden sand, while new mid-rise hotels jostle across the frontage road, next to classic two-story buildings of White City vintage. Tel Aviv has become a twenty-first century cosmo sensation.

And these sophisticated urbanites are mostly oblivious that just 30 kilometres to the east (about 20 miles) is the all-Palestinian city of Qalqiliya, surrounded by an 8-metre high wall with its 50,000+ population virtually imprisoned there by Israel’s Apartheid policies. Such are the dichotomies of the Jewish State.

The ride north is easy, following the promenade for about eight kilometres until it peters out just before Hertzliya Pituach, an upper class seafront enclave favoured by the diplomatic class and nouveau riche Israelis. I cut through the edge of the town then join route 2, the main highway north.

It is a glorious day with temperatures hovering in the mid-teens. The sun is shining but the air is a bit cool with a steady 8-10 kilometer/hour headwind. My plan is to go straight north on the route 2 highway. Technically illegal for a bicycle but it has a wide shoulder to help keep me safe.I stop at an ‘Arcaffe’, Israel’s version of Starbucks. Time for brunch and a work session at the laptop. Two hours passes quickly and I am back on the road.

Oops – roadworks ahead, completely obliterating the hard shoulder. After bouncing though the roadworks for a while, I give up and make a detour to route 4, a parallel road a few kilometres inland. This will add another hour or more to the day’s cycling. I call my host Zohar to let her know I will be a bit late. There are plans for the evening that I don’t want to miss.

Route 4 has a decent hard shoulder but a head wind gets a bit stronger – not too strong but enough to slow progress a bit. I slog on.

Finally I arrive in Atlit, a coastal village just south of Haifa. Two of my ‘besties’, Danny & Zohar, have lived there for decades. My relationship with them goes back to my earliest activities opposing the Occupation during the second Intifada twenty years ago, when Danny and I were working with the Jewish/Arab resistance (non-violent) group, Ta’ayush. We met when helping deliver food to besieged Palestinian villages that had been blockaded by the Israeli military by bulldozing huge mounds of rubble and dirt across all access roads to dozens of villages. This was my earliest ventures in the field as an activist, and I recall being mildly terrified as we lugged bags of rice past heavily armed Israeli soldiers over the mounds of dirt to the hungry villagers in the village.

I arrive in Atlit a bit earlier that I thought and after resting a bit, we bundled into their car to attend a pro-democracy rally near Netanyahu’s home in Caesariya. Danny is scheduled to sing there.

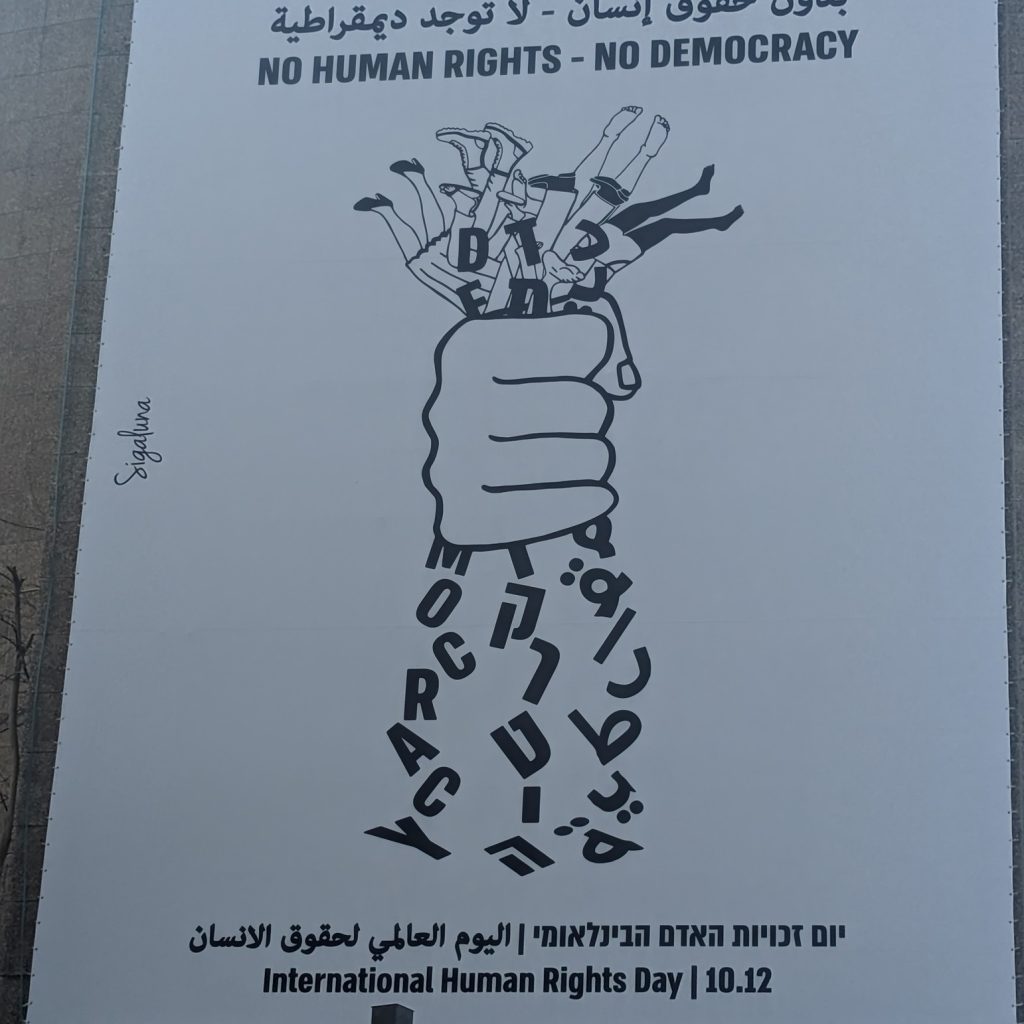

The event is slightly underwhelming both in size and political scope. Danny plays guitar and sings a few songs. Two to three hundred upper middle class locals attend, chanting pro-democracy slogans in opposition to Bibi’s government’s intention to restrict the authority of Israel’s highest court by allowing a simple majority of Israel’s parliament, the Knesset, to overturn any court decision. Another step down the slippery slope towards authoritarianism and perhaps worse. The good people of Caesariya feel they are protecting democracy but actually (in my view) are trying to ensure democracy and the rule of law for Jews. It was a Zionist event. Israeli flags were everywhere as these ‘liberals’ expressed their wish for a continued democratic Jewish rule of the country. ‘Democracy’ in Israel and Palestine is a relative concept.

It should be noted that no democratic country in Europe or elsewhere, has mandated in law, that one ethnic or religious group should rule the state. Only Israel is getting away with this medieval concept in the 21st century. However the present state of affairs has nudged my hosts to the very edge of ‘leftist’ Zionism, which acknowledges that the country will need to evolve into a single state of some sort with equal rights for everyone. They also believe that somehow a shared state for Muslims, Christians and Jews, will still guarantee that any Jew in the world can immigrate. Wishful thinking methinks . . . .

And so the day ends with the crowd singing Kumbaya (actually HaTikvah) and walking home to their villas believing they have done their bit as good Jewish citizens. Wake up people! Too little. Too late. The ship of state is sinking and likely needs to sink and be purified in the cleansing ocean of world opinion, human rights and liberal democratic values.

In the meanwhile we have to live through a dark period of illiberalism before the rebirth. May the universe have mercy of the poor souls of Israel and Palestine. Despite the madness surrounding me, I sleep well.

Comment (0)