By Miri –

During the celebrations for the 64th anniversary of Israel’s independence in 2012, a number of left wing activists from the Israeli non-profit organisation “Zochrot” were prevented by the police to hold an alternative event to commemorate the conquest and destruction of more than 400 Palestinian villages and towns through Israeli forces. One activist was arrested and had to spend the night in jail for publicly reading out the names of those places from a history book. Shortly after, a discussion was held in the Knesset, the Israeli parliament, in order to shed light on the events. In the course of this discussion then Minister of Culture Limor Livnat expressed her anger about a certain realisation:

I viewed Zochrtot’s website on my iPhone and saw a number of items, including places. Which Arab villages is Zochrot talking about, the ones they’re trying to present to the public? The public should know what they’re talking about. They show a map, with dots. Dots, dots, dots. […] Dots, from the north of the country to the south, south of Beersheva. And these dots, which are the villages they’re referring to, these dots are located everywhere in the state of Israel. Not in Judea and Samaria, not in Gaza, not in what you call the “occupied territories,” […] Here, inside Tel Aviv! I found some like that in the Tel Aviv area, dozens of dots.

|

| The Manshiyyah neighbourhood |

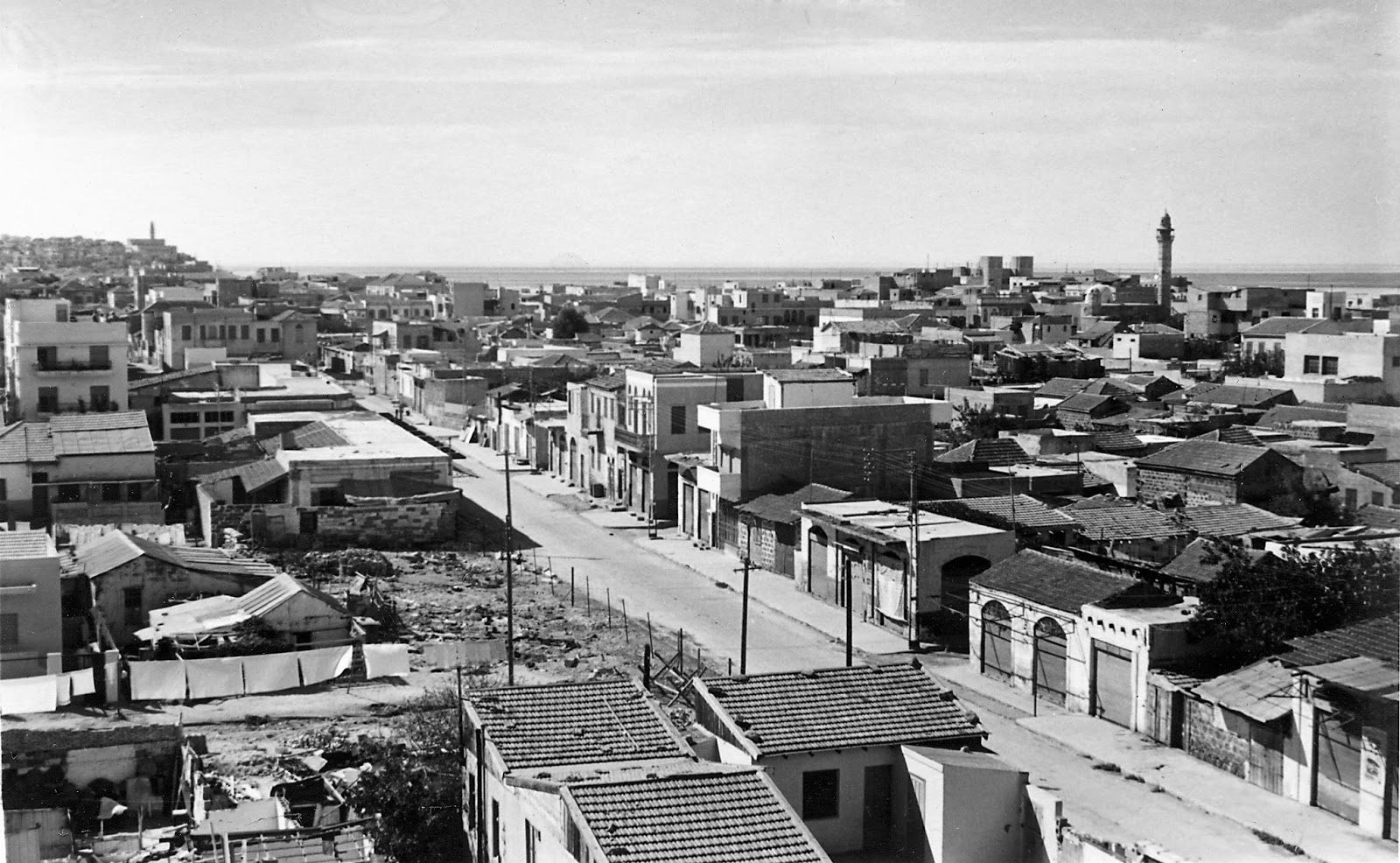

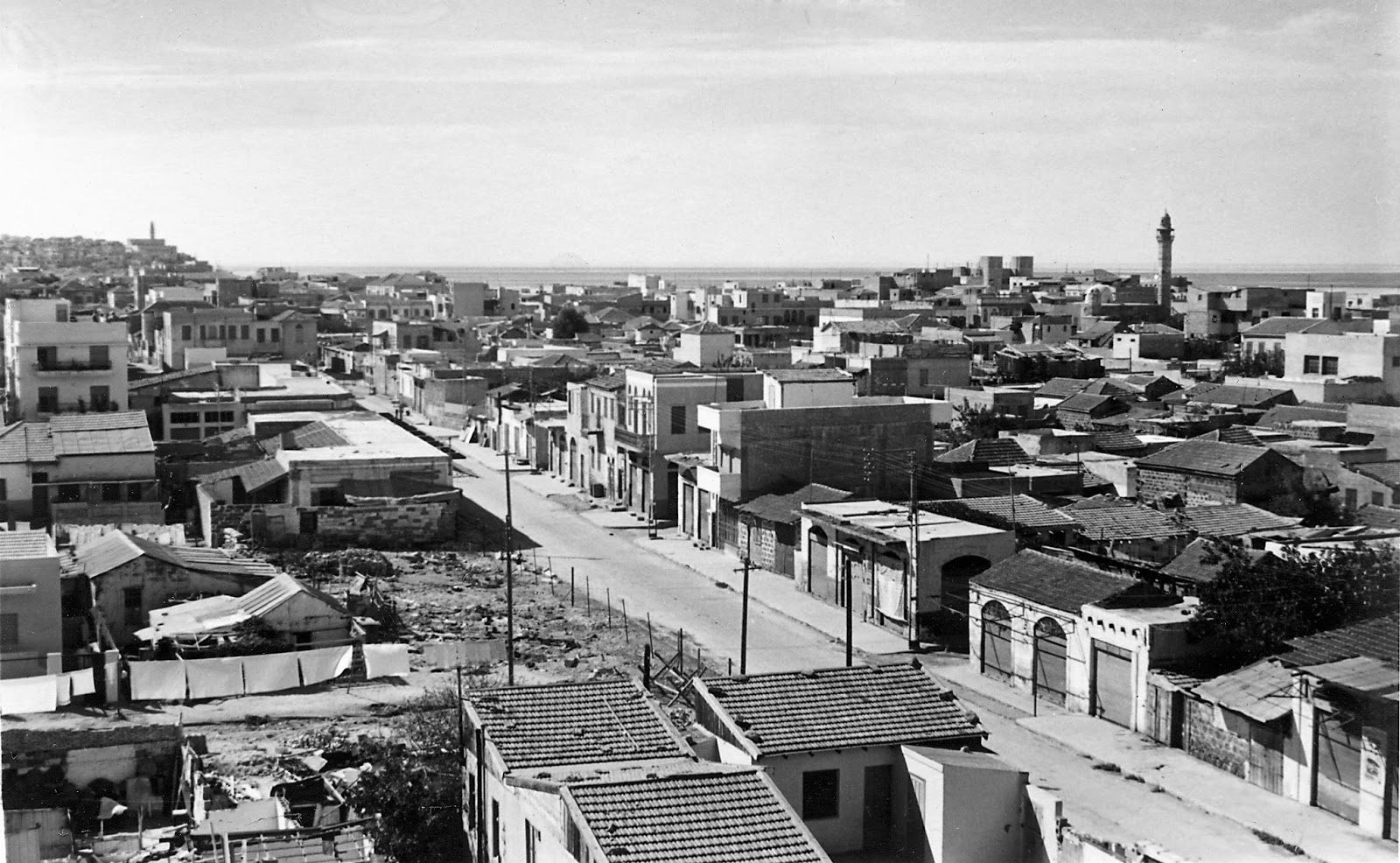

One of the dots that Livnat saw on Zochrot’s map specifies the location of the neighbourhood of Manshiyyah, once a part of the city of Jaffa, now buried underneath the asphalt of Tel Aviv. A densely built neighbourhood inhabited by 15,000 Jews, Muslims, and Christians, Manshiyyah stretched all along the seashore, from Tel Aviv’s Carmel Market up until the city walls of Jaffa. In 1948, the paramilitary organisation Irgun launched an attack against the neighbourhood in order to pave their way into the city centre of Jaffa, which was thereafter conquered. Like in the rest of Jaffa, most of Manshiyyah’s residents fled to Gaza, others to Jordan, Lebanon and further places.

Many of us believe that justice and peace will never prevail in this land unless Israeli Jews acknowledge the pain that was inflicted on the Palestinian people in 1948. But like Limor Livnat, many Israelis simply dismiss the Palestinian narrative of 1948, the Nakba, (Arabic: catastrophe) and instead believe that most Palestinians left their homes voluntarily in order to give way to the Arab armies, which supposedly promised “to drive the Jews into the sea” and reclaim Palestine for its native population. Like Livnat they are oblivious to the fact that the city of Tel Aviv was not built on sand, as is claimed by the dominant Zionist discourse, but was in fact superimposed on Palestinian agricultural lands and villages.

|

| The Map of Echoing Yafa |

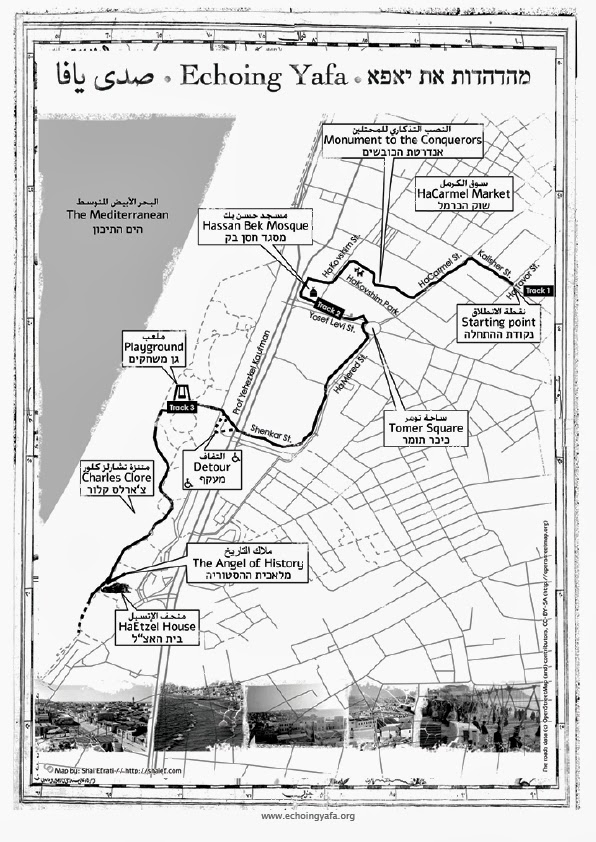

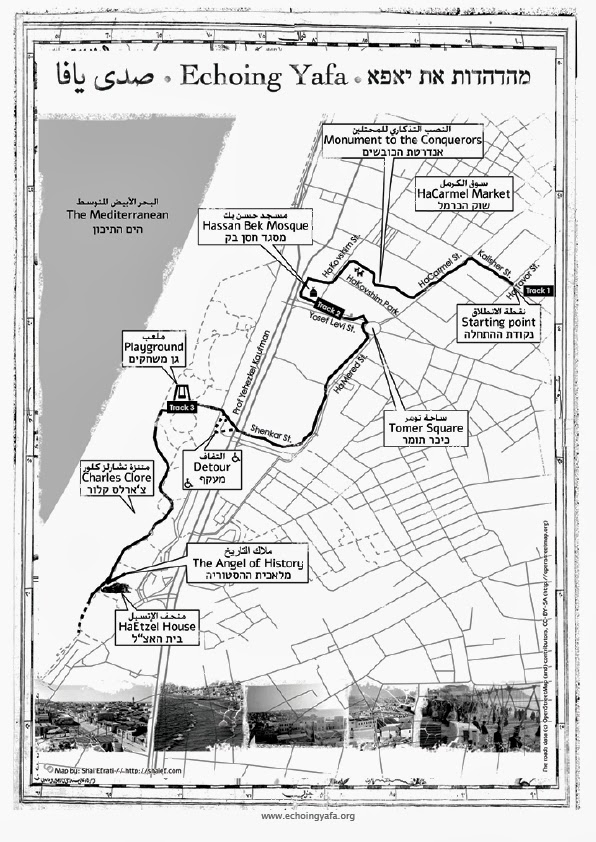

Based on these thoughts I set out to develop a project, which would bring Manshiyyah back into people’s consciousness. During the course of two years I worked on Echoing Yafa, an audio tour through the former neighbourhood of Manshiyyah. Many people thought it strange that I would solely rely on sound to reconstruct the neighbourhood, but I feel that in a society so overstimulated by images this actually made a lot of sense. Seeing usually implies a distance or detachment from the perceived event, which enables its objectification through the viewer, and ultimately very often to an undoubted representation of truth. Hearing, on the other hand, necessarily involves the full immersion of the subject into the perceived event; it is full of doubt and therefore has the potential to blur and to complicate otherwise stable mythologies, and categorisations of “us” and “them”, of “winners” and “losers”.

Together with a Palestinian colleague I started looking for former residents of the neighbourhood and asked them to tell us the stories of the life, destruction and transformation of Manshiyyah, which, together with archive material, I would later turn into a narrative. The outcome is a 50 minutes walk during which the listener meets different characters, enacted by 19 professional and non-professional local actresses and actors, who tell of their experiences and perspectives, point out and describe specific sites and events of the physically no longer present neighbourhood, that is being reconstructed in the listener’s ear. Layers of sounds, narratives, and comments, as well as site-specific music pieces, created by a number of acclaimed local sound artists and musicians, overlap with the visual experience of the listener, and move her/him in and out of her/his experience and between the past and present of the site.

Comment (0)