– by Alexander Jones –

To celebrate the launch of our tours in Hebrew to the Ajami neighbourhood in the south of Jaffa, we’re reviewing the immensely popular 2009 film of the same name. The film tells the interconnected tales of a dozen or so Ajami residents who all battle the various social challenges which plague the area. In this way the neighbourhood itself becomes the protagonist, overshadowing even the complex, interesting, and relatable characters themselves. Let’s explore the neighbourhood a little more now.

In the mid-1800s, after thousands of years of existing mostly as a walled city, the ancient port town of Jaffa began to expand quickly into new areas beyond the crumbling walls. Ajami was founded directly to the south of the old city, initially by Maronite Christians but named after a companion of the Prophet Mohammad who is said to be buried near the Ibrahim al-Ajami Mosque. This religious intermixing is typical of Ajami throughout its history, and continues to this day with Muslims, Christians and Jews all calling it home. Historically the neighbourhood was affluent, reflecting the money of those (mostly Christian) merchants wealthy enough to buy land and build mansions beyond the safety of the former city limits. During the 1948 nakba (catastrophe), when tens of thousands of Palestinians fled or were driven out of Jaffa and the surrounding villages, the 3000-4000 people who remained were shepherded into Ajami which was turned into an Arab ghetto by the nascent Israeli military. Some lived in shacks between the mansions, others divided up the bigger houses and shared them between families. Hundreds of properties were confiscated from the original Palestinian owners by the government under Israel’s infamous 1950 Absentee Property Law, and as Jewish refugees arrived from Europe, North Africa and the Middle East they were often given these properties as their own. Fenced off by barbed wire and under martial law until 1966, the Palestinians of Ajami were eventually given Israeli citizenship and on paper have almost all of same rights as a Jewish Israeli, although gross prejudice and racism still plagues Israeli society. As may be expected, problems like crime, drugs, poverty and racism still deeply effect Ajami today. You can read more about Ajami, Jaffa, and its relationship with Tel Aviv in this blog article.

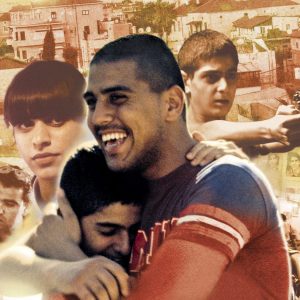

The film itself was directed by Scandar Copti, an Arab-Israeli-Christian himself born and raised in Jaffa, and Yaron Shani, an Israeli-Jew. Beyond these two pros the film relies heavily on untrained actors from the neighbourhood. This absolutely works, with several turning in impressive performances, and overall lending the film an almost documentary feeling. It’s also another way in which ‘Ajami’ is so much more than just the title of the movie.

Ajami doesn’t reduce its characters into a dichotomy but instead makes a deliberate attempt to show their problems from multiple angles and humanise them while we observe their decision making. ‘Al-shabab’ (the young, Arab men) quickly go from oppressed victims to petty and violent when they grossly overact to a request from a Jewish neighbour for peace and quiet; while the macho, rule breaking, Jewish Israeli police officer is much more than just a cardboard cut out example of the Occupation, as we see him mourning his murdered brother or tenderly bathing his elderly father. In this way Ajami may remind you of the great American TV show The Wire, which takes a shot at the system rather than the individuals forced to act and react within it. Another comparison may be drawn with the 2002 Brazilian crime drama Cidade de Deus (City of God), a film which also tells the story of a difficult neighbourhood by interweaving the stories of dozens of connected characters.

As a piece of cinema Ajami is thrilling and engaging in equal measure, while the satisfying way the disparate stories are brought together as it progresses makes for a very enjoyable ride. We don’t get to spend a huge amount of time with any one character, but this doesn’t stop them from endearing themselves to viewers. The situation appears so grim, with the odds of success stacked so heavily against Ajami’s residents, that it’s hard not root for the underdog.

There is a side of the nieghbourhood Ajami seems to willfully neglect to show – the rich. Whether Arab or Jewish, one of the unique aspects of Ajami is that interspersed between donkeys, chickens and tin shacks, are luxury mansions owned by a cross section of Israeli society. This is disappointing because it is the one area where Ajami breaks from its hyper-realistic style. With good editing and location selection it is not difficult to make Ajami seem as rough as a Rio favela. Many parts are. But pull out the camera out slightly further and you will see a grand old Palestinian villa lived in by a large Arab family, or a modern, sea-facing block of condos, sold mostly to overseas Jews as investment properties. The influx of money (much of it from foreign sources, but not exclusively) into Ajami in recent years has made it impossible for the new generation to afford property, either to rent or buy. And yes, there is of course an ethno-religious angle to all of this and the current socio-economic situation is forcing many of Ajami’s Arab residents to look elsewhere to raise their families. When racism, economics and politics combine to drive gentrification it makes for an unstoppable force. Indeed, many young Palestinians today talk about a ‘Second Nakba’ as the gentrification of Ajami and other parts of Jaffa totally transform their neighbourhoods. Despite this issue dominating Ajami the neighbourhood, it is conspicuously absent from Ajami the film. The twelve years which have passed since the movie was released could partially explain this omission, but it would be naive to think that this process has begun so recently.

Ajami is nevertheless a wonderful film which does an excellent job presenting a part of Tel Aviv that few tourists will ever visit. It is highly recommended as much to cinema lovers as to anyone interested in Israeli/Palestinian society. You can watch the full film, for free, with subtitles in your choice of 26 languages, at this link. Please note we are not responsible for outside content.

You can explore Ajami virtually once a week on our online Jaffa tour, or now in person by booking a Hebrew tour – both with our expert guide Karin. You can also contact us for customised itineraries exploring the issues raised in this article.

Comment (0)