By Miri –

Since their forced displacement from Palestine in 1948, the scattered Palestinian refugee community has been severely affected by pretty much all of the major conflicts that have been shaking the region, many times leading them to flee their newly established homes yet another time. Escaping the violence in their host countries, be it Kuwait or Lebanon, many of those refugees resettled in Syria, which, compared to other Arab states, was viewed as one of the most stable, and most sympathetic states towards the Palestinian refugees – until recently.

Manifold Odysseys to Syria

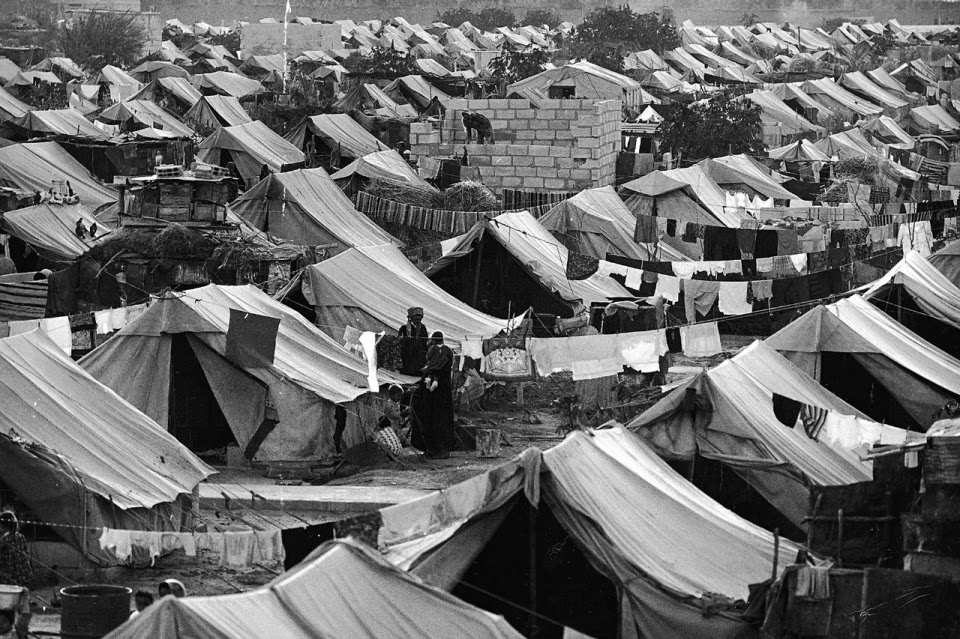

|

| Palestinian refugee camp 1948 (UNRWA Archive) |

In 1948 an estimated number of 85,000-90,000 Palestinians, mostly from northern cities and towns, such as Safad, Haifa, Acre, Tiberias, and Nazareth fled to Syria. After concentrating along the border area with Israel, and hoping to return to their homes, the refugees were later moved to live in deserted military barracks in Sweida, Aleppo, Homs and Hama.

During the Six Day War in 1967, the Black September in Jordan in 1970, and Israel’s invasion of Lebanon in 1982, the Palestinian community in Syria grew considerably and by now constitutes of nearly half a million registered refugees, equalling just over two percent of the overall Syrian population. Most of these refugees live in one of the 14 refugee camps in Syria, half of which are located in and around Damascus .

In 1956 the Syrian government adopted Law No. 260, which states that

Palestinians residing in Syria as of the date of the publication of this law are to be considered as originally Syrian in all things covered by the law and legally valid regulations connected with the right to employment, commerce, and national service, while preserving their original nationality.

The law thus basically implies that the Syrian government officially opposes the permanent re-settlement of Palestinian refugees on Syrian soil, and instead insists that the only acceptable solution is constituted by the return to their homeland. The Syrian government was thereafter celebrated as having “gradually paved the way for [the refugees’] thorough integration into the socioeconomic structure while preserving their separate Palestinian identity”.

Notwithstanding the relatively fair approach towards the refugees, previous long-term president Hafez al-Assad, is said to have systematically used the Palestinian resistance as a political tool and, in order to not challenge his own hegemonic position within the area, to have prevented the emergence of a Palestinian power centre. In pursuance of furthering Syrian control over the Palestinian leadership, the former president allegedly “instigated divisions and created his own Palestinian proxies” and even backed assaults on Palestinian refugee camps in Lebanon during the civil war.

Historically Palestinian activism in Syria was limited to themes and events directly relating to their own national cause, yet with the start of the uprising in March 2011, more and more Palestinians increasingly abandoned their neutral stance towards the despotic Assad regime, and instead started identifying with the Syrian cause.

Palestinians and the Syrian Uprising

During the first year of the Syrian uprising the Palestinian communities were only indirectly affected, and mainly suffered collateral damages from the invasions of the cities in which the refugee camps are situated. Considering themselves as “guests” of Syria, they still abstained from openly engaging with the ongoing conflict, yet from the beginning of the revolution, Palestinian camps allegedly served as safe havens for the wounded and displaced Syrians.

Similarly, the Palestinian leadership in the West Bank and Gaza tried to officially stay neutral in order not to harm the communities trapped in Syria. Hamas left their Syrian headquarters in early 2012, reportedly silently protesting against the Syrian regime’s violent response to the uprising.

However with an intensification of the fighting, especially young Palestinians felt more and more drawn to the side of the opposition and increasingly started clashing with the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine – General Command (PFLP -GC), a splinter group of the older PFLP which has been acting as an extension of the Assad regime inside the refugee camps.

|

| Yarmouk Camp, Damascus, 2013 |

In December 2012, fighting between the Free Syrian Army, supported by one of their Palestinian subsections, the Liwa al-Asifah (the Storm Brigade), and the PFLP-GC ensued in the Yarmouk refugee camp. Yarmouk is one of the unofficial refugee camps in the south of Damascus, and until the uprising, used to be the home of the largest Palestinian community in Syria.

In response to the fighting, the Syrian army for the first time started directly targeting a refugee camp, with army jets bombing Yarmouk and killing at least 23 civilians. Those air strikes are said to have finally “shattered what was left of the Syrian government’s claim to be a champion and protector of Palestinians“.

|

| Solidarity protest in Ramallah, 2014 |

With the camp coming under the control of the Free Syrian Army and its allies, the Syrian regime placed Yarmouk under total siege. Except for one food parcel, which was recently allowed to enter the camp in January 2014, all humanitarian aid, including the delivery of food and medicine was blocked since July 2013. According to the UN at least 43 residents of Yarmouk camp have died of starvation; Palestinians sources who managed to sneak out of the besieged camp speak of more than 100 deaths.

As of October 2013, 120,000 of the 140,000 Palestinian residents of Yarmouk have escaped the fighting in the camp.

A total number of 235,000 Palestinians have been displaced in Syria itself and 60,000, alongside 2.2 million Syrians, have fled the country.

According to the Working Group for Palestinians in Syria 1597 Palestinians were killed, with 74 of those deaths being caused by severe torture in Syrian prisons.

Another 651 Palestinians are said to be imprisoned or to have “disappeared“.

Comment (0)