By Miri –

“The thing about football – the important thing about football – is that it is not just about football.”

Terry Pratchett

A few years back many Palestinians would have asked me, the obvious foreigner, about my political opinion, be it on the Occupation as a whole, or on international or internal Palestinian politics.

These days I much more often encounter the question “Barcelona or Real Madrid?”. The same sentiment is mirrored on the walls of many Palestinian city, town and village, which traditionally marked the territory of the respective dominant party, which, in recent years, would be most likely either Hamas or Fatah. These days the walls frequently tell you whether you are entering the home base of either Barcelona or Real Madrid fans. It makes me think whether the Palestinian population grew so weary of this inner political division that has been paralysing the country for so long that they replaced it with the more exciting rivalry between those two Spanish football clubs. At least you always have a winner.

I have tried to, but could not find an explanation of why the Palestinians chose those particular two teams, but seemingly it is unheard of, or at least extremely unpopular to support any other team. Except for a Palestinian one, of course.

|

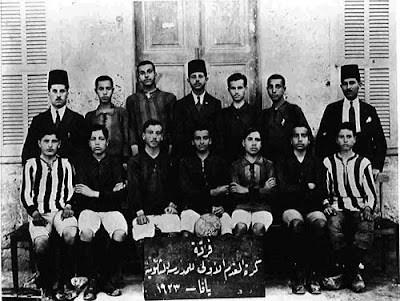

| Football team of the Government Secondary Boys’ School, Jaffa, 1923. |

One may think this whole football craze is a rather recent phenomenon and a result of increasing globalisation forces, but in fact the earliest record of football being played in Palestine is a 1906 match between Jewish youth and a visiting group of French sailors

In addition, Palestine has also one of the oldest histories in organised football in the Middle East.

As early as 1928, the Palestine/Eretz Israel Football Association was founded and joined the FIFA in 1929. In the beginning the association included both Arab-Palestinian and Jewish clubs, in addition to teams made up of British police men and soldiers serving under the British Mandate. Yet, with increasing tensions between the local Palestinian population and the Zionist movement, the Arab clubs were soon phased out by the association and therefore reorganised themselves in 1931 as the Arab Palestine Sports Federation, which took more than fifty clubs under its umbrella.

With the creation of the state of Israel and the concomitant expulsion of more than 700,000 Palestinian Arabs in 1948, Palestinian football culture obviously received a huge blow. At the same time, the Palestinian refugee camps, especially in the countries of Lebanon, Syria and Jordan reportedly overflowed with football talent and benefitted the national leagues in the respective country.

As late as 1998, and contingent upon the establishment of the Palestinian Authority, Palestine applied and was admitted into the FIFA and became part of the Asian Football Confederation (AFC). At that time, the

Israel Football Association, on the other hand, had already been long expelled from the same AFC due to pressure from other Arab and Muslim members who refused to play against the Jewish State. After a long hiatus, Israel was admitted to the Union of European Football Associations (UEFA) in 1992.In this sense, at least as far as sports are concerned, the Middle East conflict is overthrowing geography and designating Palestine as a part of Asia, and Israel as a part of Europe.

1

|

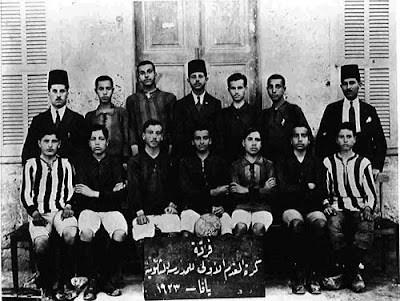

| Jimmy Turk |

While it is pretty unlikely that the Palestinian and the Israeli national team will encounter each other on the playing field any time soon (both are not yet successful enough to qualify for the World Cup), individual players from both sides play against, but also with each other in the Israeli national league.

Rifaat “Jimmy” Turk, a native of Jaffa, came to be the first Palestinian citizen of Israel to also play in the Israeli national team in 1973, and in 1980 was voted Israel’s player of the year. Yet, throughout his career, and reportedly during basically every game, Turk had to bear racist remarks from parts of the Israeli audience2.

After Jimmy Turk, many more Palestinians entered the Israeli Premier League, but it was not until 1996, that a predominantly Palestinian team from inside Israel, Hapoel Taybeh, was promoted to the top division. Finally in 2004, Bnei Sakhnin became the first Palestinian owned club to win the Israeli State Cup.

In addition to the racism that many Palestinian players experience, the case of upcoming football star Ali Khatib testified to another set of difficulties that Palestinians may face when joining an Israeli club. Khatib, also a Palestinian citizen of Israel, was charged with treason when leaving the West Bank league and his East Jerusalem team Jabal Mukaber in order to play for the Israeli club Hapoel Haifa. Khatib further outraged his Palestinian fans with a statement in which he expressed his intention to play in the Israeli national team.

From a career opportunity point of view, Khatib’s move is understandable; playing in the Israeli league, as opposed to the West Bank or Gaza league, opens up more possibilities for any player, be it a Palestinian or an Israeli. Yet from a political point of view the outrage of Palestinian football fans is also very justified.

|

Prisoner Poster of Mahmoud Sarsak, Gaza, 2012

|

Due to the arbitrary travel restrictions imposed on Palestinians by the Israeli authorities, Palestinian football faces a huge amount of difficulties, including even the organisation of training sessions for the national team, the team’s participation in international tournaments, or the playing of matches between clubs from Gaza and the West Bank. In other instances, football infrastructure, such as Gaza’s only football stadium was destroyed in an Israeli air strike in 2006.

More recently, former Palestinian national team player Mahmoud Sarsak from Gaza brought both the topic of Palestinian football and the continuity of human rights abuses against the Palestinian population to international attention, when he joined the hunger strike of Palestinian prisoners to protest against the unlawful practice of administrative detention, which allows for indefinite custody without trial or charges. After more than three months on hunger strike, Sarsak agreed to sign a deal which eventually set him free after three years in Israeli custody.

Returning to Terry Pratchett’s opening quote, football in Palestine and Israel is definitely not just about football. On the one hand it may have the potential to build bridges between individual people, yet at the same time it also provides a mirror which painfully shows the severity of the overall situation, which cannot be solved by bringing together a bunch of Palestinian and Israeli kids to kick a ball together.

1 The same is also true for some international cultural competitions. Israel, as a member of the European Broadcasting Company, has for instance been a long time and successful participant of the Eurovision Song Contest.

2 To be fair, it should be noted that football all over the world is suffering from a severe racism problem and the New Israel Fund, admittedly a rather progressive force for Israeli standards, together with the Israeli Football Association, has even launched a programme to combat racism from within the stands.

Comment (0)