By Miri –

Like Palestinian artistic and cultural forms of expression in general, Palestinian cinema is “structurally exilic”, meaning its actors are spread across different places, with limited means of communication and collaboration. As such the cinematic approaches of Palestinian film makers, just like their backgrounds, differ considerably, yet writer Nana Asfour asserts that “[w]hat binds Palestinian films together are the language – Palestinian Arabic – the subject – Palestinian lives – and the desire of each director to portray his [sic] own take on what being Palestinian means”.

|

| The Alhamra Cinema in Jaffa, 1937 |

Another commonality according to Asfour is that Palestinian cinema in all its forms can be described as an act of resistance against the effort of being made invisible and in defiance of Israel’s attempts to systematically prevent the emergence of Palestinian culture. Considering the conditions under which Palestinians especially in the West Bank and Gaza, and to a lesser extent in Israel live, the very existence of a stateless cinema is in fact remarkable. Until recently there was hardly any national funding, relatively few skilled crews and film makers frequently had to work around curfews and roadblocks, and were not always able to access their locations. And yet, against all odds, Palestinian cinema has been steadily developing and increasingly receives international attention.

According to Nurith Gertz and George Khleifi, the history of Palestinian cinema to date can be divided into four different periods.

The founding moment of Palestinian cinema is usually set in the year 1935, with Ibrahim Hassan Sirhan’s short documentary about King Ibn Saud of Saudi Arabia’s visit to Palestine. Sirhan produced two more documentaries and in 1945 established the film company “Palestine Studio”, which however produced only one feature film “Holiday Eve”, which was unfortunately lost in 1948, when Sirhan had to flee his home in Jaffa.

The second period, from 1948 to 1967 is labelled by the authors “the epoch of silence”. The only nascent Palestinian film industry had just been destroyed and its potential agents were spread across the globe, merely coming to terms with their new existence as “subordinates and marginalized subjects in alien countries”. While new documentaries on the Palestinian dilemma started to emerge especially in Egypt, the centre of the Arabic speaking film industry, only few exiled Palestinians, such as Muhammad Saleh al-Kayyal, who lived in Egypt, had the opportunity to partake in those endeavours and were able to make their own voices heard.

|

| “Palestinian Cinema – An Essential Front in Our Struggle” |

Lasting between 1968 and 1982, the third period is described as “the revolutionary period”, which saw the emergence of a number of mainly documentary films, produced by Palestinian political movements in exile. Realising the potential of the medium to advance the Palestinian cause and to influence public opinion in the West, the Palestinian Liberation Organisation founded Aflam Filasteen (Palestinian Films) in Jordan in 1968. A small crew, including Sulafa Jadallah, the first camerawoman in the Arab world, borrowed film equipment and set out to document military actions, revolutionary events, the Palestinian resistance, and everyday life in the refugee camps. Those revolutionary film makers adopted the style of newsreels, blending scenes of destruction with victory speeches and song, “transforming every Palestinian defeat into victory – and thereby providing a sort of ‘correction’ of the past”.

In 1973, the short-lived non-partisan Palestinian Cinema Group was founded, whose stated goal was “to develop a Palestinian cinema capable of supporting with dignity the struggle of our people, revealing the actual facts of our situation and describing the stages of our Arab and Palestinian struggle to liberate our land”. At the same time the group’s manifesto also propagated “the emergence of a new aesthetic”, which at the time however was not realised.

The revolutionary period produced more than sixty documentaries, many of which were however lost after the 1982 Israeli invasion of Beirut, the location of the PLO’s film archive .

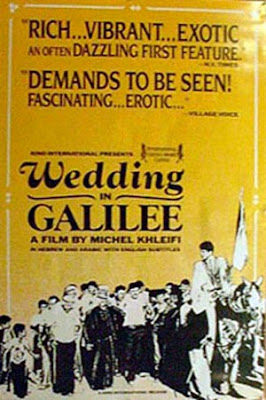

Finally, the fourth period begins in 1982 and lasts until the present day. While the films of the previous period aimed at depicting the Palestinians as one unified nation, suffering from a unifying trauma, the new era of Palestinian cinema finally saw the emergence of personal and individual stories. Michel Khleifi (Fertile Memory 1980, Wedding in Galilee 1987, Canticle of the Stones 1989) is usually credited with launching the new Palestinian cinema by directing Wedding in Galilee, the first feature film by a Palestinian. While depicting the intervention of Israeli rule on daily Palestinian life, the film also illustrated Palestinian society’s own oppressiveness, criticising particularly its patriarchal structures.

Finally, the fourth period begins in 1982 and lasts until the present day. While the films of the previous period aimed at depicting the Palestinians as one unified nation, suffering from a unifying trauma, the new era of Palestinian cinema finally saw the emergence of personal and individual stories. Michel Khleifi (Fertile Memory 1980, Wedding in Galilee 1987, Canticle of the Stones 1989) is usually credited with launching the new Palestinian cinema by directing Wedding in Galilee, the first feature film by a Palestinian. While depicting the intervention of Israeli rule on daily Palestinian life, the film also illustrated Palestinian society’s own oppressiveness, criticising particularly its patriarchal structures. In 1993 Rashid Masharawi (Curfew 1993, Haifa 1995, Ticket to Jerusalem 2002, Laila’s Birthday 2009) released his debut Curfew, set within a family home during a seemingly endless curfew in Gaza, and highlighted the despairing and constrictive reality of Palestinian refugees. Finally in 1996, Elia Suleiman made himself internationally known with his Chronicle of a Disappearance, and soon became the most celebrated Palestinian film maker. In 2002 the submission of his Divine Intervention was rejected by the Academy on the grounds that Palestine did not constitute a nation. Hany Abu-Assad’s (Rana’s Wedding 2003, Paradise Now 2005, Omar 2013) Paradise Now, a co-production between Palestinians and Israelis, managed to enter the competition, running under the label “Palestinian Authority”. Scandar Copti’s Ajami constituted the first predominantly Arabic-language film submitted by Israel for the Academy Award.

|

| Still from Abu-Assad’s Paradise Now |

This points to a general difficulty of Palestinian film makers, many of who are citizens of Israel, and who by receiving funding from Israeli institutions, or by working with Israeli film teams, continue to be criticised for collaborating with the occupier, and whitewashing the Israeli state. Most recently Palestinian actor Saleh Bakri, the son of one of Palestinian cinema’s most prominent actors, Muhammad Bakri, said in an interview that he opposed the way his appearance in Israeli films has been manipulated to “make Israel look good” and to appear as a diverse and democratic state.

The Israeli criticism on the other hand focusses mainly on a perceived lack of “fleshed out Israeli characters” in Palestinian films, which seems hypocritical at best, considering the very one-dimensional portrayals of Palestinians in the majority of Israeli film productions. As such, “by driving [the Israelis] out of the cinematic frame”, Palestinian film makers can also be seen as expressing “resistance to the hegemonic might of the rulers”.

Criticism has also been launched from the Palestinian audience, who felt offended by some of the film makers’ denunciation of elements in the Palestinian society. However, much more difficult than bearing their criticism, is the fact that most Palestinian film makers cannot reach the people they are talking about. Due to a complete lack of movie theatres in Gaza, and only a few in the West Bank, any European will have greater access to Palestinian films than the vast majority of Palestinians.

Notwithstanding all those difficulties and the fact that “the war of images”, just like the war of the occupation seem to continue to be in Israel’s favour, Nana Asfour is hopeful: “the number of Palestinians who believe in the redemptive power of the image – and of narration – is ever-growing”, and will in the future also include more and more female film makers. While there are already a number of documentaries and short films made by Palestinian women, Annemarie Jacir’s Salt of this Sea (2008), constituted the first feature film made by a Palestinian woman. Already her second feature When I Saw You was selected as the Palestinian entry for the Best Foreign Language Oscar in 2012.

Comment (0)