By Miri –

Growing up in Germany mainly amongst non-Jewish friends, together we developed a pattern of translating Jewish holidays into Christian ones. “So when is your Jewish Christmas?” my friends would ask me, referring to Hanukka, which obviously has absolutely nothing to do with the Christian holiday except for its similar timing around December. While I was developing an independent and pretty proud Jewish identity, I would sometimes get offended by the referral and reduction of the older Jewish holidays to the more recent Christian ones. Yet, as with pretty much every other cultural practice around the world, Christians have borrowed from Jews, whose traditions in turn were shaped and influenced by other communities, by historical events etc. Although the pace of globalisation is being undoubtedly accelerated through the introduction of modern media, especially the internet, it really is not a new dynamic and no culture can claim to have evolved completely autonomously.

|

| Jewish girls dressed up for Purim, Poland 1938 |

The Jewish holiday of Purim which is being celebrated during these days is a good case in point. Although from a Jewish religious point of view a minor holiday, it is probably one of the most beloved and most fun ones, for children, because it involves making noise at the synagogue, eating a lot of sweet stuff and more importantly dressing up in costumes, a tradition most likely introduced by Italian Jews at the end of the 15th century and hailing from the Roman carnival. Grown ups probably primarily enjoy the fact that we are “compelled” by scripture to get drunk.

At the same time, beyond the happy festivities, the story behind the holiday as narrated in the Megillat Esther, the Scroll of Esther, gives us the opportunity to connect this holiday to a whole lot of broader issues.

Here is a short summary of the Megillat Ester:

|

| Esther before Ahasuerus, Artemisia Gentileschi, Italy 1593–1651/53) |

During a six-month drinking feast given by Ahasuerus, King of Persia (generally identified as Xerxes I of Persia) for his army, the king orders his wife Queen Vashti to display her beauty in front of his guests. After her refusal, the king decides to remove Vashti from her post and orders all beautiful young women to parade in front of him so he can choose a new queen.

King Ahasuerus picks Esther, a Jewish orphan who was raised by her older cousin Mordecai. The same Mordecai soon calls the attention of Haman, the king’s prime minister, when he refuses to bow down in front of him, explaining that he was a Jew, and as a Jew he was not allowed to bow in front of men. Enraged by Mordecai’s disrespectful behaviour, Haman decides to punish him by killing the entire Jewish minority of the empire. Haman even obtains permission for his revenge plan from the king, who is oblivious to the fact that his own wife is Jewish as well. The same night the king learns that Mordecai had previously prevented the plan of some courtiers to kill him and that he had not received any recognition for saving the king’s life. The king thus consults with Haman about how to honour the man. In the belief that the king is talking about himself, Haman proposes that the honoree should be dressed in the royal robes and parade on the king’s royal horse. Upon realising that the honoree is the detested Mordecai, Haman’s rage only grows.

During the same evening Esther reveals Haman’s plan to the king, as well as her own Jewish identity. Ahasuerus orders Haman to be hanged instead of Mordecai. Since he cannot annulle the previous decree against the Jews, the king allows Esther and Mordecai to write a new one, which states that Jews are allowed to preemptively kill those who posed a risk to their lives. As a consequence thousands of enemies of the Jews were killed in the days following the new decree.

|

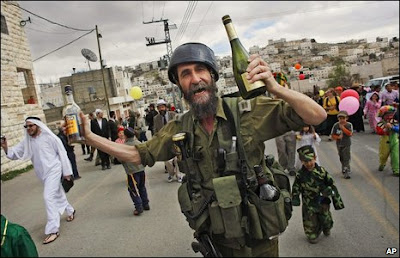

| Settler dressed as soldier parading in Hebron, Purim 2009 |

Obviously, just like any other text, the Megillat Esther can be understood in many ways. Within a national-religious context it is interpreted as a narrative about Diaspora Jews falling victim to the whims of power, and eventually, in conclusion, turn into the victors, “a fantasy of Jewish power written in a time of Jewish powerlessness”.

Most likely it is this thought of Jewish perseverance that the extremist settlers of Hebron celebrate and showcase during their annual parade through the streets of the occupied West Bank town, guarded by Israeli authorities, while the Palestinian residents can do nothing but look on.

But there are more stories to be told, and different lessons to be learned. Although the book is named after one of the female protagonists, the traditional rituals and symbols associated with Purim mainly serve to emphasise the male characters of Haman and Mordecai. One of the central rituals is the reading of the Megillah itself. While rabbinical sources stress that women should hear the Megillah since “they also were involved in that miracle”, most traditional religious authorities hold that women should not read the text by themselves, but that it should be read to them by a man.

During the reading of the Megillah every mentioning of the name Haman is to be responded by the congregation with noise-making with rattles and so on, in order to blot his name out. However, both the repeated reading of his name (54 times), as well as the noise-making eventually reaffirm Haman’s central presence, both in the story as well as in the sanctuary.

The names of Vashti and Esther figure far less prominently, yet already early Jewish feminists saw the potential of the two queens to serve as powerful role models. Esther is obviously a heroine due to her her brave “coming out” as a Jew and her courage to directly confront both the king and Haman and thereby to save her people. Vashti on the other hand, the non-Jewish queen obviously deserves to be celebrated “for her open defiance of the king and her powerful defense of her body and sexuality”. Although being not Jewish, Vashti because of her own suffering at the hands of the more powerful, i.e. men, has thus a lot in common with Esther and Mordecai. Thinking of the affinities between the two queens rather and thereby moving beyond the dichotomies of “good” versus “bad”, Jewish versus non-Jewish etc., can serve as a motivation to forge alliances and fight for the powerless in general.

A different perspective on the story, a focus on what is usually being omitted by traditional readings can thus open up more progressive meanings and lessons to be learned… maybe someone should tell the settlers in Hebron?

Happy Purim!

Comment (0)