By Miri –

Today’s Jaffa forms part of the joint Tel Aviv – Jaffa municipality, which often gives the impression of Jaffa being just another neighbourhood, or even a suburb of Tel Aviv. This widespread perception signifies quite an affront to the Bride of the Sea, Jaffa’s proud nickname. The city ranks as the second oldest inhabited settlement in the region after Jericho and thus also supersedes Jerusalem in its age.

During Jaffa’s 4000 year old history, the city has changed hands and/or has been partially or wholly destroyed no less than thirty times. Tel Aviv, whose foundation stone was officially set in 1909, really emerged out of Jaffa and should hence be considered as its little sister and not vice versa. But as with many other places in the region, the power imbalances and the competing political and historical discourses, but also urban planning and development, make it difficult to reveal an alternative version of history. Embarking on one of our new Jaffa – Tel Aviv tours will open up a different narrative and highlight the intertwined development of those two places.

Part 1 – Jaffa

|

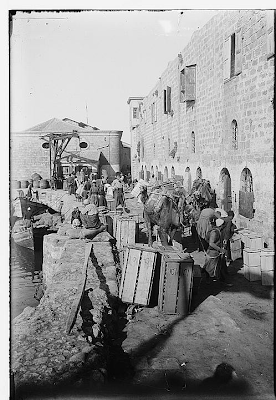

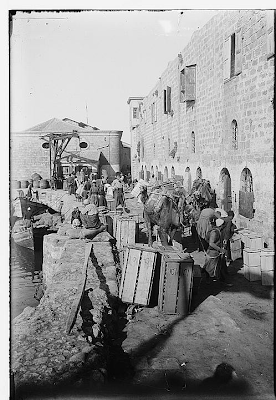

| Loading the famous Jaffa Oranges at Jaffa Port ca. 1900 |

The most significant geographical feature of Jaffa used to be its natural harbour, which constituted the only one of its kind along the whole coast line of historical Palestine. It allowed conquerors, but also the boats of traders, pilgrims and migrants to set anchor without running the danger of their boats being swept away.

If you look at Jaffa’s port today, you will probably find it hard to imagine that it once constituted one of the main connections between Europe and the Levant and that the traffic of ex- and imported goods and people was capable of competing with the ports of such metropolises as Alexandria and Beirut.

This influx created a lot of work opportunities and Jaffa became an important destination for migrants from all over the Middle East, North Africa and Europe, who settled down in the city and its environs. This in turn created a unique atmosphere of cultural heterogeneity and made Jaffa a truly cosmopolitan place. Due to the great number of migrants who came to Jaffa especially during the 19th century, the city expanded greatly beyond its walls and new neighbourhoods emerged all around it.

In order to escape the overcrowded conditions, the insufficient infrastructure and bad sanitary conditions within Jaffa, a group of Jews in 1887 also decided to create a neighbourhood beyond the walls, Neve Tzedek, which would later be included into Tel Aviv and is now considered its oldest part.

At the time of Neve Tzedek’s foundation, the Zionist movement had not yet established itself so firmly in Palestine and the Arabic speaking Jewish community of Jaffa did not distinguish itself from the rest of the population, but rather formed an integral part of cosmopolitan Jaffa. The establishment of Neve Tzedek was therefore also not intended to set the community apart from the rest of Jaffa.

With the onset of the British Mandate over Palestine after World War I, and especially with the issuing of the Balfour Declaration in 1917, which promised the establishment of a Jewish homeland within Palestine, which in turn led to increased Jewish immigration, more and more tensions arose.

Due to the growth of the Jewish population in Jaffa, the founding of Neve Tzedek set a pattern for the creation of about a dozen other Jewish neighbourhoods that would be established throughout the next two decades. In 1909, Ahuzat Bayit, another Jewish neighbourhood was founded outside of Jaffa, this time however with the intention to separate itself from the rest and to lay the foundation stone for a new and modern Jewish city – Tel Aviv.

|

| A Bauhaus building in the Ajami neighbourhood of Jaffa |

During the following decades this new city developed and expanded rapidly, but also Jaffa went through a process of renewal and development. While today’s Tel Aviv is celebrated as a UNESCO world heritage site for the greatest accumulation of Bauhaus buildings in the world, which also gave it its nickname, the White City, the beautiful Bauhaus buildings of Jaffa, some of which can still be found up until today, are rarely, if ever mentioned.

Today, after decades of neglect, Jaffa is advertised to tourists and investors as the “jewel of Tel Aviv”. This however was only made possible after large parts of the city were demolished, first by the British and then by Zionist paramilitary forces and, more importantly, after 90% of its Palestinian residents fled or were expelled during the war of 1948. Those who did not leave were concentrated in a barbed wire ghetto in Ajami, a neighbourhood that was originally founded by Maronite Christians in the 1830s. Although this neighbourhood was one of the most modern and developed ones of Jaffa before 1948, the conditions there deteriorated very fast due to neglect by the newly founded municipality of “Tel Aviv – Yafo”.

The property of those Palestinians who had fled, i.e. approximately 90% of Jaffa’s real estate, was transferred to the state and eventually became public housing, a process legally sanctioned through the implementation of the “Absentee Property Law”.

|

| Graffiti in Ajami, Arabic: “Jaffa weeps”, Hebrew: “Housing for the Arabs in Jaffa” |

Starting in the 1970s, a process of “rehabilitation”, “development” and gentrification was set in motion and soon its agents saw Jaffa’s “Oriental charme”, so rejected in the past, as having commercial potential. The restoration of old houses and the building of new projects in the “Jaffa Style” turned the area into an “Oriental Disneyland” for tourists and investors. Real-estate prices in places like Ajami started sky-rocketing, while the Palestinian community of the neighbourhood still remained one of the poorest in the whole region. In addition to that, about 500 families of the neighbourhood, whose very ground, right by the sea and in immediate proximity to Tel Aviv, is one of the most valuable ones in the country, live under the threat of home demolitions and eviction orders.

The “rehabilitation” of Jaffa thus clearly necessitated the exclusion of the Palestinian population, who in turn see it as the continuation of the Nakba (Arabic: “catastrophe”, meaning the expulsion of 1948), and its process of displacement and dispossession.

Although there is an obvious power imbalance, leading once more to the victimising of the Palestinian community, it should be noted that this process at the same time greatly contributed to a strengthening of the ties of most of the community to Jaffa and its Arab identity and mobilised it into resisting the policies imposed on them by the municipality and the Israeli state as a whole.

Part 2 – Tel Aviv

The continuation of our Jaffa – Tel Aviv tour leads us through the erased neighbourhood of

Manshiyyah, which once more challenges the notion of Tel Aviv as being built on sand. The dunes of Charles Clore Park that you will be crossing, conceals the rubble that remained from the demolition of the neighbourhood in 1948 and in the beginning of the 1960s and highlights the success of the concerted effort to erase the Nakba both from the collective Jewish-Israeli consciousness and from the landscapes of Israel.

|

| Today’s Neve Tzedek |

Manshiyya borders with Neve Tzedek, the first Jewish neighbourhood outside of Jaffa’s walls, already mentioned in the first part of this article. Although its founder, Aaron Shloushe was very critical of the Zionist movement, the neighbourhood soon became the home of many early Zionists and a centre for their activities.

After 1948 also Neve Tsedek went through a process of neglect when its earlier wealthy inhabitants left and were replaced by newly arrived immigrants from the lower strata of Jewish-Israeli society. Walking through today’s picturesque Neve Tzedek with its coffee places, galleries and restaurants, the Suzanne Dellal Centre for Modern Dance (whose buildings started out as a school, founded by the same Aaron Shloushe), makes it hard to imagine that a few decades ago this neighbourhood was considered a slum. Today, only very few of the older residents still live here. Just like the former Jewish inhabitants of Jaffa, they had been offered alternative and more modern housing, moved out and most of Neve Tzedek was sold. These days it is considered one of the most expensive neighbourhoods in the country.

Walking on and out of Neve Tzedek, we’re led to the next phase of nascent Tel Aviv and to the neighbourhoods that were built starting in 1909. Focussing more closely on the different architectural styles of those early buildings, the changing self-perception of the Jews vis-a-vis the Arab population is being revealed. While some of the earlier buildings are still built in an eclectic style, mixing elements of local Middle Eastern architecture with other styles associated with the West, the buildings erected from the 1930s onwards show a break and a clear distancing from everything Oriental, and thus a return to the Zionist project of creating “an outpost of civilization in the Middle East”. It is around that time that more and more International Style and Bauhaus buildings started penetrating the city, which were supposed to emphasise Tel Aviv’s character as a modern and Western space, more resembling European cities, than Middle Eastern ones.

|

| Postcard of Rothschild Boulevard, 1911 |

Our route leads us to Rothschild Boulevard, the Tel Avivian pendant of what was once called Jamal Pasha Boulevard, now Jerusalem Boulevard, which was described as the Jaffan answer to Tel Aviv’s European inspired boulevard.

Rothschild Boulevard, up until today constitutes the site of many crucial political events, such as the declaration of Israeli independence.

Today Rothschild Boulevard still symbolises power, above all the power of capital and both Israeli and international banks have their headquarters lined up along the boulevard. So it was also not by coincidence that the Israeli social justice movement started here, when in July 2011 a handful of people erected their tents in the middle of the boulevard to protest the rising living costs in Tel Aviv, which eventually led to one of the biggest social protests in the history of Israel. The movement, which was mainly led by young, middle class Ashkenazim (broadly meaning Jews of European origin), was and continues to be charged with failing to include those sections of society that suffer the most from the policies of the Israeli state, namely the Mizrahim (meaning Jews from the “East” understood as “Oriental Jews”), Bedouins, migrant workers and refugees, and obviously the Palestinian citizens of Israel and the Palestinians living in the West Bank and Gaza.

Moving south from the pompous boulevard, the inequalities of Israeli society become more apparent as we enter the neighbourhood of Neve Sha’anan. Although we seemingly have left Jaffa far behind, a big part of this area was also once a citrus orchard belonging to a wealthy Christian from Jaffa, whose villa, now almost completely dilapidated, can still be found.

In the 1930s Neve Sha’anan emerged just as other Tel Avivian neighbourhoods and also matched their appearance.

|

Ethiopian restaurant in Neve Sha’anan

|

|

These days, the area hardly fits the image of the “White City”. After its residents left for the wealthier neighbourhoods in the centre and the north of the city, it became the home of newly arrived immigrants mainly from the former Soviet Union. In recent years, with the onset of international labour recruitment mainly from countries, such as the Philippines, Thailand and China, more and more migrant workers moved in. More recently Neve Sha’anan also started to be a concentration area for refugees, mainly from Eritrea and Sudan.

For open minded people without reseravtions, Neve Sha’anan is a great place to discover and to learn about different food cultures, music etc.. Yet most Tel Avivians only ever rush through the area on their way to the Central Bus Station, Tel Aviv’s transportation hub located in Neve Sha’anan and mainly view the neighbourhood as a lawless twilight zone, associated with drug trade, sex work and violence.

Typically, the Tel Aviv municipality does little to alter the conditions and basically allows for the neighbourhood’s further deterioration. Yet, as we have seen in other neighbourhoods of the city, it is probably only a matter of time until Neve Sha’anan will become an object of development and rehabilitation, a playing field for investors and real-estate agents, a process which, just like in Jaffa, will necessitate the erasure of the presence of its non-White, non-Jewish elements.

Looking at Tel Aviv and Jaffa from this perspective, the myth of the White City being built on sand is easily dismantled. In order to maintain Tel Aviv’s image of a modern and European style city, Jaffa had to be discursively constructed as a primitive Oriental maze, frozen in time, a notion that exists up until today, with the only difference that this maze has become very attractive and can now be bought at the expense of the leftovers of the local community.

The Jaffa/Tel Aviv development process is mirrored throughout the country, as the Israeli government and local authorities continue to remake the landscape to conform with the Zionist vision of a Jewish State.

Comment (0)